Most pilots have experienced “differences training†in one way or another. Perhaps it was making the jump from a normally-aspirated airplane like the Cessna Centurion to its turbocharged cousin. Or switching from the proverbial “Hershey wing†Cherokee to the tapered-wing Archer.

In larger aircraft, it might come in the form of an FAA-sanctioned day of training on the differences between a Gulfstream G450 and G550 – two airplanes covered by a single type rating.

These miniature training courses are present throughout the flying world. And for the most part, they aren’t seen as a big deal. Sometimes they aren’t even referred as “differences trainingâ€. For example, many companies integrate new pilots through a process called Initial Operating Experience, or IOE. This is something I do at my own company. As an IOE captain, I help new pilots who’ve completed their ground and simulator training make their first operational flights.

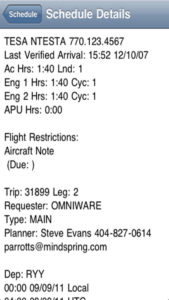

It’s kind of a bespoke process, but still recognizable as “differences trainingâ€. Some of the aviators are far more experienced on the Gulfstream IV than me, but are new to the company. With them, I’ll focus more on company procedures, especially the myriad iPhone and iPad apps we use for flight risk analysis, aeronautical charting, flight planning, weight & balance, dispatching, company manuals, and filing flight logs.

Other IOE candidates might be long-time pilots with the company, but are new to this particular aircraft type. So while they’re up to speed on our SOPs, a bit of mentoring on the peculiarities of the G-IV might be required.

Over time, I’ve come to realize that differences training is well named, because it can make the difference between safe and unsafe operation. It can even be the root cause of an accident. As I look back at the Gulfstream IV’s 30+ year operational history, I can see at least a couple of accidents which are directly attributable to a lack of differences training. One was a 1996 event in Chicago where differences in how pilots at two separate companies handled a nosewheel steering switch became a factor in the airplane’s loss of control.

Airline vs. Charter Captain: Big Differences

More recently, in 2012 a Gulfstream IV was lost in southern France during a short re-positioning leg. The aircraft, operated by Universal Jet Aviation, was flying from Nice-Cote d’Azur Airport (LFMN) to Le Castellet (LFMQ) with just the two pilots and a flight attendant aboard. The SIC was flying from the right seat.

After performing a visual approach to runway 13, the main landing gear touched down just about where it should have. There were almost 4,000 feet of runway remaining. The nose gear, however, did not touch the ground for another 1,500 feet, and when it did, it then came up off the ground again. The airplane began drifting to the right, the nose was forced down, and a swerve to the left caused the jet to exit the left side of the runway about 1,250 feet from the end of the pavement. It hit a metal fence and a stand of trees, catching fire and consuming the airframe. The three occupants perished in the crash.

The accident investigation was conducted by the Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses — the French equivalent of our NTSB. If you’re interested in reading it, an English version of the full report is available online. In addition, I highly recommend James Albright’s analysis.

There were a number of factors in this crash, but the ones of most interest to me are those surrounding the pilot-in-command, a retired American Airlines 777 captain who was hired by Universal as a captain on the G-IV. As I’ve said many times, human error is responsible for nearly 90% of accidents, so that’s where it makes most sense to focus our energy and attention.

As a former long-haul airline pilot, he had been advanced quickly to PIC status on the Gulfstream IV. The problem is that on-demand charter flying is a world apart from flying a 777 from major airport to major airport. And there are indications the transition was proving to be a challenge:

Several UJT pilots who flew with the Captain said he was not accustomed to short flights. They also agreed in stating that he was not comfortable with handling the FMS, carrying out checklists and in his role as Pilot Monitoring in general. He had a strong personality and sometimes imposed his decisions. Two co-pilots who flew with him reported that he had already forgotten to arm the ground spoilers.

This seems pertinent considering the following:

-

- The runway at Le Castellet is just over 5,000 feet long — on the short side, but well within the G-IV’s capability. While he had been to Le Castellet previously, it may have been shorter than he was comfortable with, especially given that he was not physically flying.

- The leg from Nice to Le Castellet is about 85 nautical miles. An average 777 leg is thousands of miles long, but the Gulfstream often makes extremely short flights. Van Nuys to Burbank. Santa Monica to Los Angeles International. Teterboro to Newark. The workload is very high on these legs because everything has to be compressed into a few short minutes. It’s easy to fall behind, especially for the non-flying pilot. As a result, short flights are more risky if not handled properly.

- The PIC had an established history of forgetting to arm the ground spoilers on the Gulfstream IV. This is a major oversight, as without the spoilers the weight of the aircraft is not fully on the wheels after touchdown.

- The accident report highlighted training inadequacies, specifically the lack of no-ground-spoiler landings in the sim. The handling characteristics of the Gulfstream IV are markedly different when the ground spoilers fail to deploy.

- Airline indoc and training takes several months, whereas in charter/corporate it’s done within weeks.

- Part 135 flying involves going anywhere at any time rather than flying a smaller, pre-specified route network on a schedule.

- Often, charter pilots swap seats as well as legs. At the airlines, the FO never sits in

the left seat.

If I had to distill this mishap down to a single bullet point, I’d say it was the fact that the captain wasn’t capable of accomplishing everything that needed to be done. He wasn’t flying this leg, but he was mentoring a less experienced pilot who was. That’s a whole other boatload of work in and of itself. And it had to be done while doing all the non-flying tasks in the cockpit: handling radios, checklists, programming the FMS, configuring the airplane, and so on. That’s why the non-flying pilot has a much higher workload than the one physically manipulating the controls.

Universal is a highly experienced operator; you’d think they would understand that 30,000 hours in a long-haul 777 doesn’t prepare a pilot for the 135 shtick. But this sort of thing happens all the time — and not just in bizjets.

I remember checking out a successful and decorated former F-4 carrier pilot in a Pitts S-2B and thinking it would be relatively easy because he was quite good with the Super Decathlon and had plenty of aerobatic competition experience. The reality? He’s the only guy I was never able to sign off to solo the Pitts. He just wasn’t fast enough on the rudder to maintain control, no matter what I tried. It always struck me as odd, because he performed plenty of carrier night landings in a large, heavy fighter onto a short, pitching deck.

Anyway, perhaps differences training aimed at transitioning a widebody airline captain into a charter PIC would have avoided the Le Castellet accident. If I was designing such a course, it would highlight short runways, uncontrolled fields, circling approaches, and short legs – all the things an experienced 777 captain never does.

The takeaway is this: every flying job requires a different set of skills. The final stages of training should be carefully and thoughtfully tailored to each candidate’s individual needs. We make assumptions based on a pilot’s previous experience or total flight time at our peril.

The shortest leg I ever flew was DFW – DAL. We took off south left turn and were on final for Love. I was PNF in a Citation XL. Five minute leg and after turning off the landing runway I was out of breath.

That *is* a short one! Isn’t it amazing how you can literally be out of breath after sitting strapped into a seat for five minutes? It’s not like there was anything physically strenuous about the flight, but the mental work, the division of attention and the rate at which things happen are such that a short flight can be more exhausting than a long one.

One of my favs was flying from L.A. to New York, dropping passengers at Teterboro, and then re-positioning the aircraft to Newark, White Plains, or other nearby airport. HPN was particularly dicey because the tower is closed, it’s dark, there’s construction going on at the airport, and the runway sits in somewhat of a black hole. Oh, and it’s the end of a relatively long day.

Among the many well-written and informative aviation articles that Ron Rapp has posted this may be the best. After 4 years of fun in the F-4 Phantom I ended up in the Learjet Far Part 135 world and found it to be far more challenging than flying the F-4. My memoir, The Rogue Aviator, chronicles a plethora of radical jaw-dropping scenarios. I later spent 22 years as a 727 Captain with too many airlines and found the straight scheduled service to be a walk-in-the-park compared to flying a Learjet min-fuel ADF approach at 3 am into a 4,000 foot runway on the side of a mountain in Latin America.

You summarized the difference between airline and corp/charter flying even more succinctly than I did, Ace. It’s interesting how little scheduled airline flying has changed over the past 50 years. The *lifestyle* has changed for airline pilots, but the nature of the job has been pretty consistent. In many ways that’s a good thing I suppose.

On the other hand, business aviation has changed dramatically over that same time period. I’ve met airline guys who’ve told me with a straight face that it’s impossible for anyone flying charter to make a six figure salary and if I claimed differently, I had to be lying. In fact, I think that was stated in some of the comments on one of the posts here on this site.

I thought they were joking until I realized their conception of charter is limited to a low-time CFI flying a clapped-out Apache or Navajo on an occasional single-pilot trip with a local businessman to some not-to-distant locale to build multi time. The reality of a today’s G650s and BBJs as business airplanes is beyond their worldview.

I don’t think this represents the typical airline pilot, but just the idea that someone who works in the aviation industry could believe such a thing in 2016 is amazing. Even first officers new to jet aircraft make six figures these days in business aviation. Not all of them, but many of the ones I fly with do. And they earn every penny with those 3 a.m. circling approaches into god-knows-where. If you want challenge, that’s a good place to find it.

Thanks for the reminder, also: I need to get your book! 🙂

I dread those short flights. We just did one from HPN to TEB after a 10 hour trip from Africa. I try to get everything set up before taxi, ATIS, approach, ILS , final approach course (oops!) missed that one. Everything was fine until nobody answered when we were switched off to New York approach so finally I had to call Teterboro tower. He clears us to land but then gets upset that we were not handed over from New York approach. We were high and made S-turns and ultimatly realized we were lined up for runway 24, not 19! We were cleared to land on 24 but what a mess! I think the whole flight was 7 or 8 minutes!

Btw, I used to fly with a pilot that flew with that captain when he started flying the G4. He said the guy was horrible, wouldn’t listen to anyone, totally out of sync with charter operations. He would freak out if the copilot told the line people to service the lavatory, “that was the captains job”!!! Anyway, he also had a really bad habit of STRONGLY PUSHING FORWARD ON THE YOKE AFTER THE NOSEWHEEL TOUCHED DOWN because thats what he did on the 777. Go figure, that may have played a factor in this tragedy.

I feel your pain on that short leg, Art. It seems to be the one thing that never gets any easier, no matter how many hours I rack up in the Gulfstream or on a particular route. There’s always some curve ball that comes with it. A runway change, a communication challenge, runway lights that don’t work right, a wind shift, odd traffic conflicts, shortcuts or reroutes — the list is long and varied. And as you noted, those short ones are often the final leg of a really long and exhausting day. Sometimes I find it hard to go to sleep after those short legs because I’m still kind of amped up even after we get to the hotel.

Interesting anecdote regarding the pilot of that flight. I suppose the lesson is that every airplane is different, and applying the techniques used on your old aircraft to a new type can be a very bad idea. I wonder if the landing criteria used in the simulator played a role. After all, the way we land a G-IV in real life is not the way they have us do it in the simulator with those spot landing requirements. So perhaps the artificiality of the simulator sessions masked a poor technique that a sim instructor would have been able to stamp out if only they’d been able to see it.