“No one realizes how beautiful it is to travel until he comes home and rests his head on his old, familiar pillow.†–Lin Yutang

Even before I started flying for a living, traveling internationally always made me appreciate what we have here at home. Most people are aware of the hassles involved with long-distance international journeys: you’ve gotta consider passports, visas, different electrical outlets and voltages, language barriers, currency exchange, jet lag, and more. Perhaps that’s one of the reasons traveling the world can be so rewarding: much like flying, it’s not easy. You’ve got to earn it.

When you’re the one doing the flying, things are even more complicated. If you’ve followed the travails of any of the Earthrounders – people who fly light GA aircraft around the world, often to raise money or set some kind of record – you’ll notice they all have one thing in common: an inordinate number of delays, problems, and hassles in transiting from one country to another. Given the fact that those of us who do it for a living are not only more experienced with international operations, but also have professional dispatchers, handlers, and staff behind us, you’d think we’d eventually surmount these obstacles.

You’d be wrong.

I recently participated in a series of trips which took our airplane to China and back – twice – and then eastbound across the world to explore Africa before coming home. It once again reminded me of what incredible barriers humans can erect to keep would-be travelers tied up in bureaucratic knots.

Here are just a few examples:

Visas. Sometimes we need them, sometimes not. Other times crew members have their own specific visa requirements. If you get it wrong, you’ll find yourself missing that flight you were supposed to be on. It’s an especially big problem if you were the one who was supposed to be piloting the plane! There are some countries where even with the right paperwork, you’ll be denied entry if they see you’ve been to a country with which they’re on unfriendly terms.

Customs. It’s bad everywhere, but this might be one place where returning to the U.S. is the worst. I once had a passenger manifest consisting of a half-dozen U.S. Customs agents. I figured we’d breeze through the clearance process upon returning to the United States – after all, these guys had diplomatic passports and active Immigration & Customs Enforcement credentials. The reality? We had to shut down the aircraft, offload all luggage, and traipse across a large airport to clear Customs. One of our passengers was detained briefly because he had a “common nameâ€. I was baffled. If Customs doesn’t trust Customs agents from their own department, there’s something wrong.

Handlers. When flying internationally, we hire professionals who specialize in dealing with the local procedures, folks who know the ropes and speak the language. They arrange our fueling, interface with ramp personnel, airport employees, drivers, and so on. They handle the paperwork and speed us on our way. Or not. Some handlers do a great job, others are awful. On one trip I handed off the aircraft to a subsequent crew who were literally held up – detained — for a cash “fee†by the handler who was supposed to be keeping just that sort of thing from happening. It’s like being robbed at gunpoint by your own bank.

Flight planning. In the United States, we take many things for granted. Altitudes are given in feet. Speeds are expressed in knots or miles per hour. Fuel is dispensed in gallons. Once you venture abroad, you’ll find countries which utilize things like meters, hectopascals, and liters. I haven’t seen cubits or fathoms used yet, but it wouldn’t surprise me. There are places where altitudes are sometimes in meters, other times in feet. And they don’t always tell you which you’re being given. In certain countries, usually those with plenty of mountainous terrain, altitudes are referenced to the airport elevation rather than sea level. It’s easy to confuse terms like QNH, QFE, and QNE. Get it wrong in those places and you can find yourself flying into the side of a mountain!

Paperwork. In the U.S., we can get weather information from a wide variety of sources, from telephone briefings to iPhone apps. Abroad, you’ll find yourself forced to purchase, if not use, their weather products. You’ll be required to obtain various stamps and approvals. This can involve long waits and unexpected delays. Indians seem to love their paperwork more than just about anyone I’ve seen. Overflight or landing permits can take days, sometimes weeks to obtain. In countries like China or Russia, there are no short-notice trips for private or business aircraft because they’re impossible. Change your plans? Running late? You’re just out of luck.

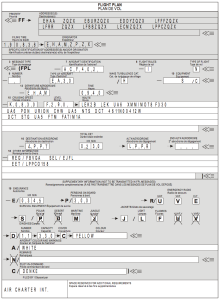

Even in Europe, flights can require slot reservations, much the way special events like the Super Bowl do here in the U.S. If you miss your slot time, you go to the bottom of the list. Have you ever seen an ICAO international flight plan form? I’ve seen one wrong mark on this form ground a flight for hours.

Costs. Landing, ramp, and other fees can be dramatically higher in foreign countries than in the United States. This extends to things like catering, water & lav services, and even plain old ice. In Geneva, an Italian pilot with whom I used to fly reported paying more than $1,000 to have a bag of ice delivered to the aircraft.

Ramp checks. You think having an FAA inspector ask for your pilot certificate and medical is bad? Try the European equivalent, a SAFA (Safety Assessment of Foreign Aircraft) check. A team of inspectors will crawl all over the interior and exterior of the aircraft, checking emergency exits, altimeters, flight recorders, navigation charts, emergency equipment, pilot training records, placards, and everything else you can possibly think of.

Accessibility. We take it for granted that you can fly VFR anywhere you want in the U.S., even at night. We can go to the busiest airports, and they are prohibited from discriminating against general aviation or any class of operator. Many countries do not allow VFR at night, single engine IFR, experimental aircraft, aerobatics, or GA flight over populated areas.

Don’t get me wrong, there’s plenty to love about international travel, but the process of flying abroad is usually far more expensive, slow, and cumbersome than it needs to be. If you’re the guy in the left seat, it’s best to take to heart the words of Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu, who prophetically stated that “a good traveler has no fixed plans, and is not intent on arriving.â€

Though for very different reasons, whether I’m landing at home or abroad, I always end up thinking to myself, “What a country!â€

AMEN, Brother! (Pan American World Airways, Ret.)

A Clipper veteran! You must have a virtual book of international flying tales. What’s the craziest story on your list?

I am growing to understand the pains of flying internationally in my new location. Being military provides a whole different set of challenges. It can be a lot of fun when you get there, but it can be a ton of work getting there.

I would think you’d have an especially interesting set of challenges, with the combination of military and civilian regulations AND the international differences. Does the military provide additional support for international trips?

There is definitely some support, but much of it is left up to us to figure out. My personal favorite is ATC trying to vector us across countries we don’t have clearance for so they can charge us for their services. Sometimes I think it is just them trying to help, but other times it is intentional. Maybe that isn’t just a military thing though.

I doubt it’s just a military thing, although I don’t think I’ve ever been vectored over another country just to ring up charges. Or maybe I have and I just didn’t know it…

When you don’t get the bill it is easy to not know.