I don’t know who first described flying as “hours of boredom punctuated by moments of sheer terrorâ€, but it wouldn’t be shocking to discover the genesis was related to flying a long-haul jet. I was cogitating on that during a recent overnight flight to Brazil. While it was enjoyable, this red-eye brought to mind the complacency which can accompany endless hours of straight-and-level flying – especially when an autopilot is involved.

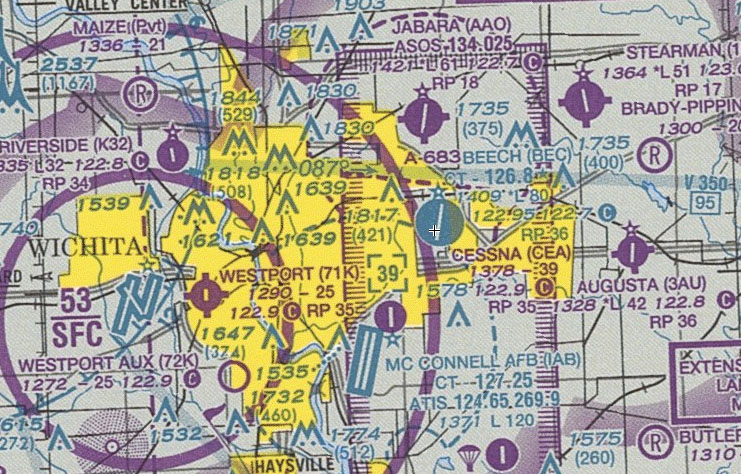

This post was halfway written when my inbox lit up with stories of a Boeing Dreamlifter – that’s a 747 modified to carry 787 fuselages — landing at the wrong airport in Wichita, Kansas. The filed destination was McConnell AFB, but the crew mistakenly landed at the smaller Jabara Airport about nine miles north. The radio exchanges between the Dreamlifter crew and the tower controller at McConnell show how disoriented the pilots were. Even five minutes after they had landed, the crew still thought they were at Cessna Aircraft Field (CEA) instead of Jabara.

As a pilot, by definition I live in a glass house and will therefore refrain from throwing stones. But the incident provides a good opportunity to review the perils of what’s known as “expectation biasâ€, the idea that we often see and hear what we expect to rather than what is actually happening.

Obviously this can be bad for any number of reasons. Expecting the gear to come down, a landing clearance to be issued, or that controller to clear you across a runway because that’s the way you’ve experience it a thousand times before can lead to aircraft damage, landing without a clearance, a runway incursion, or worse.

I’d imagine this is particularly challenging for airline pilots, as they fly to a more limited number of airports than those of us who work for charter companies whose OpSpecs allow for worldwide operation. Flying the Gulfstream means my next destination could be literally anywhere: a tiny Midwestern airfield, an island in the middle of the Pacific, an ice runway in the Antarctic, or even someplace you’d really never expect to go. Pyongyang, anyone?

But that’s atypical for most general aviation, airline, and corporate pilots. Usually there are a familiar set of destinations for a company airplane and an established route network for Part 121 operators. Though private GA pilots can go pretty much anywhere, we tend to have our “regular” destinations, too: a favored spot for golfing, the proverbial $100 hamburger, a vacation, or that holiday visit with the family. It can take on a comfortable, been-there-done-that quality which sets us up for expectation bias. Familiarity may lead to contempt for ordinary mortals, but the consequences can be far worse for aviators.

One could make the case that the worse accident in aviation history – the Tenerife disaster – was caused, at least in part, by expectation bias. The captain of a KLM 747 expected a Pan Am jumbo jet would be clear of the runway even though he couldn’t see it due to fog. Unfortunately, the Clipper 747 had missed their turnoff. Result? Nearly six hundred dead.

The Dreamlifter incident brought to mind an eerily similar trip I made to Wichita a couple of years ago. It was a diminutive thirty-five mile hop from Hutchinson Municipal (HUT) to Jabara Airport (AAO) in the Gulfstream IV. We were unhurried, well-rested, and flying on a calm, cloudless day with just a bit of haze. The expectation was that we were in for a quick, easy flight.

We were cleared for the visual approach and told to change to the advisory frequency. Winds favored a left-hand pattern for runway 36. Looking out the left-hand window of the airplane revealed multiple airports, each with a single north-south runway. I knew they were there, but reviewing a chart didn’t prepare me for how easily Cessna, Beech, and Jabara airports could be mistaken for one another.

We did not land at the wrong airport, but the hair on the back of my neck went up. It was instantly clear that, like Indiana Jones, we were being presented a golden opportunity to “choose poorly”. We reverted back to basic VFR pilotage skills and carefully verified via multiple landmarks and the aircraft’s navigation display that this was, indeed, the correct airfield.

That sounds easy to do, but there’s pressure inducted by the fact that this left downwind puts the airplane on a direct collision course with McConnell Air Force Base’s class Delta airspace and also crosses the patterns of several other fields. In addition, Mid-Continent’s Class C airspace is nearby and vigilance is required in that direction as well. Wichita might not sound like the kind of place where a lovely VMC day would require you to bring your “A†game, but it is.

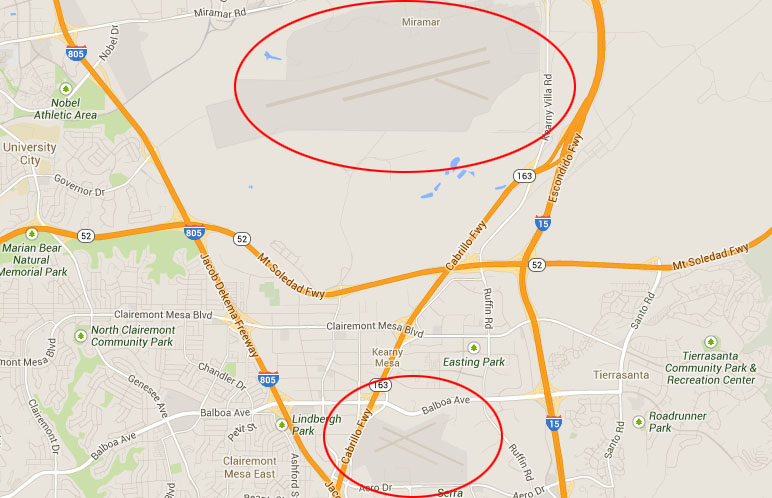

Expectation bias can be found almost anywhere. I’d bet a fair number of readers have experienced this phenomenon first-hand. In my neck of the woods, MCAS Miramar (NKX) is often mistaken for the nearby Montgomery Field (MYF). Both airports have two parallel runways and a single diagonal runway. Miramar is larger and therefore often visually acquired before Montgomery, and since it’s in the general vicinity of where an airfield of very similar configuration is expected, the pilot who trusts, but – in the words of President Reagan – does not verify, can find themselves on the receiving end of a free military escort upon arrival.

Landing safely at the wrong airport presents greater hazard to one’s certificate than to life-and-limb, but don’t let that fool you; expectation bias is always lurking and can bite hard if you let it. Stay alert, assume nothing, expect the unexpected. As the saying goes, you’re not paranoid if they really are out to get you!

This article first appeared on the AOPA Opinion Leaders blog at http://blog.aopa.org/opinionleaders/2013/12/03/expectation-bias/.

Great post, Ron. In my field, this one gets scientists, too. An experiment works out the way someone expects and they may jump to conclusions that the data support their thinking. The solution to this is a well designed experiment with good negative and positive (where available) controls and the discipline to seek alternative explanations (hypotheses) that also explain the data, but can be eliminated through further experimentation. Your example of other airports near the destination are the pilot’s equivalent to those alternative hypotheses and care must be taken to eliminate them, using all the tools available, from a paper chart to a GPS. I wonder how much of expectation basis (or, for that matter, confirmation bias) can be mitigated with thorough preflight planning (e.g., to build awareness of potential for confusion)?

And no, I will cast no stones, either. I still remember my student solo cross country on a hazy day when I mistook a small Class E field for the larger towered field that was my destination. Fortunately for me, the runway configurations were nothing alike and I realized my error quickly (i.e., before I did anything stupid).

Thorough preflight planning can certainly play a role in mitigating confirmation or expectation bias. That’s how I noticed the runway similarities in Wichita, although the planning didn’t fully prepare me for what it would look like out the window once I was airborne.

I believe the real key to avoiding expectation bias is a certain level of cautiousness or skepticism. That mild paranoia naturally leads us to seek out additional data to confirm our suspicions. Using the “wrong runway” situation as an example, other sources of information might come from a navigation display, querying the controller, asking the other pilot what they are seeing, and of course good old fashioned visual pilotage. That’s easy to do when you’re in doubt. It’s far more difficult to force oneself to continue looking for confirming data when you’re certain you are correct.

I feel for the flight crew in this situation. The unfortunate thing about flying is that you can do it right a thousand times and nobody says a word. But get it wrong just once, and even if there’s no damage and no injuries, you’ll be hung out to dry. They say flying is intolerant of errors, but sometimes the aviation community can be doubly so.

Excellent observation and relation to science, Chris. Confirmation bias is something that can bite us in many aspects of our daily lives, for which we should remain vigilant.

When I worked at Rapid City Regional airport it was a daily occurrence that someone would head for nearby Ellsworth Air Force base. The airbase sticks out like a sore thumb and the civilian airport is hard to see. A couple Delta pilots landed at the airbase and got fired.

This seems to be fairly common when civilian and military airports are in relatively close proximity. The runways are frequently oriented in the same direction since the prevailing wind is similar, and because military airfields tend to be longer and larger than their GA counterparts, they are visually acquired by the pilot first. Target fixation sets in, and they focus on landing there.

If the pilot is local, they probably know the area and are less likely to land in the wrong place. It’s the unfamiliar, transient aviator who needs to keep a sharp eye out for this kind of thing.

I have to applaud you for “not throwing stones” in your “glass house”. This is a well written, make-you-thinker! And I remember the first time I flew to MYF, Mirimar was rather tempting at first! But like you said, VFR Pilotage is very important, even to somebody who mainly flies instruments.

Thanks for the kind words, Scott! Glad you enjoyed the post…

Yes, the importance of visual pilotage to an instrument pilot is not often broached during IFR training, is it? We who teach instruments spend a lot of time on circling maneuvers and whatnot, when the far more common scenario is “cleared for the visual”. Perhaps a few case studies on the pitfalls of the visual approach procedure, if nothing else.

Good article and helpful observations.

When I flew freight, our company policy was that if there was an instrument approach to the runway on which we were landing, we were to have the approach chart briefed and the appropriate frequencies loaded or the approach activated on the GPS. Even if we were in VFR conditions, making a visual approach. That policy kept many a pilot not only from landing at the wrong airport, it kept them from landing at the correct airport, but on the wrong runway.

One more observation: When Regan spoke the words “trust, but verify …” while visiting the former USSR, he was in fact quoting Gorbachev, who was quoting Vladmir Lenin, who liked the old Russian proverb. By speaking those words, Regan was making a sort of inside joke, but the publicity combined with a lack of historical context, leading some who revered Regan to believe the phrase was his original creation. Given “trust, but verify” was one of Lenin’s favorite phrases and that Lenin was one of the seminal communist figures only serves to deepen the irony.

How interesting! I knew “doveryai no proveryai” was a Lenin quote, but didn’t realize Reagan had gotten it from Gorbachev. The aphorism has a rare distinction of sounding good in both languages.

Re: your company’s policy, it’s smart to have an approach briefed whether you use it or not. I’ve been to many places where our weather datalink and the D-ATIS assure from hundreds (if not thousands) of miles away that it’s clear and a million, only to find upon arrival that it looks much different from the air. The setting sun, haze, and other things can really throw a wrench in the viz.

Even if it’s truly “clear”, airports can hide in plain sight at times. Having an instrument approach procedure ready to go is just smart; it assures that all available resources are being used.

Besides, Murphy’s Law dictates that once you’ve taken the time and effort to brief and set up the approach, it probably won’t be needed. 🙂

…it kept them from landing at the correct airport, but on the wrong runway I can remember a flight landing on a taxiway one early morning at Atlanta a few years ago…

I trusted my son’s Christmas party to be at 10 am in the morning (as all previous parties were) but I did verify with the teacher only to find that it was re-scheduled at 4 pm…

As Murphy also said, if something can go wrong, it will!

When I was doing my own flight training at Jabara in the late ’90s, I worked as a line service tech there to pay for flight time. Everybody who worked at the airport had stories of way-too-large aircraft enroute to McConnell/Boeing landing at that wrong little executive airport. Although I haven’t confirmed it, one of them was an Antonov. Yikes!

I remember flying into Fort Lauderdale Exec (FXE) a bunch of years ago. I was flying with two other flying buddies, but we had been flying most of the day, and it was now around 2 or 3 a.m. Approach called out the airport at our 12 o’clock and however many miles, and the three of us thought we had it in sight. (You have to understand…pretty much the entire east coast of Florida is awash with lights at night, with airports every few miles, and nearly all the airports have east-west and southeast-northwest runways.) A friend of mine was flying; I was in the right seat as we reported the field in sight, changed to advisory frequency and entered a right downwind. Wait a minute…as I looked over, I saw that the southeast-northwest runway was not lighted, whereas I knew from prior experience that both runways at FXE were lit. I told the PF that I thought we were at Pompano, and just as he added power, Approach contacted us on FXE’s frequency and said, “Grumman XXX, I think I misled you when you said you had the airport in sight. Looks like you’re at Pompano.” That controller was really on the ball!

But I agree with John who talked about loading the approaches, even when making a visual. After that experience, I did likewise!