In a world full of world records, endurance — or “time aloft” — has been a prominent metric going back to the very genesis of powered flight. Even today you can see granite signposts along the Wright brothers flightpath at Kitty Hawk, marking the distance and time achieved by each successive attempt on that historic day. Powered flight was only a few hours old and already the race was on!

The Draw

I’ve been fascinated by endurance records for a long time. For one thing, these feats highlight the tremendous achievements of technology. Voyager’s around-the-world flight in 1986 is but one well-known example. Composite technology allowed that 900 pound aircraft to carry 9,000 pounds of fuel, enough to more than double the previous non-stop record of 12,532 nm. Of course, it took them just over nine days to do it. Nine days! Imagine spending that long trapped with another person in a cockpit the size of a phone booth, a screaming engine just a couple of feet behind you. Oh, and your noise-cancelling headset circuitry failed. Insulation? There was none — remember, the each pound of added weight required nine more pounds of fuel to carry it around the globe.

The closest I’ve come to endurance flying would be a 15.7 flight hour, three-leg westbound coast-to-coast flight in a normally aspirated Skylane in 2002. During my years at the California Medfly Project, my logbook indicates I’d fly as much as 8.6 hours in a day. Today, I do plenty of long-haul flying on the Gulfstream, although it’s a bit easier on autopilot at 45,000 feet than it was hand-flying all day at low altitude in the U-21A.

Speaking of records, the new Gulfstream G650 recently set a record, circumnavigating the globe westbound in 41 hours. They did it in relatively cushy surroundings, as you can see in this video. Beds for the off-duty pilots, a full galley, and a stand-up cabin with multiple lavatories.

Human Interest

At their heart, these records are usually stories of human endurance rather than anything mechanical. It’s not even about the flying, really. A drone staying aloft for a year wouldn’t be nearly as amazing as a human doing it for half that length of time. Which is more impressive, a satellite orbiting the planet for a decade, or Russian cosmonaut Valeri Polyakov remaining aboard space station Mir for 437 straight days? Polyakov, by the way, has logged a total of 678 days in space. Imagine how much solar radiation his body has absorbed!

This month’s Blogging in Formation topic was “aviation history”, and since yours truly is last on the list I can look back and see that every post in the group was, at it’s heart, about people more than anything else. For example, Karlene’s topic was the amazing support her spouse provides; Brent wrote about the courage of Spitfire reconnaissance pilots during World War II; Dan mused about gender bias and Jerrie Mock’s pioneering 1964 around-the-world flight.

The Mother of All Endurance Records

One of the best parts about endurance flying is that, unlike speed, altitude, time-to-climb, and other such records, you needn’t spent millions of dollars. It all about determination. In fact, despite modern space-age technology, the all-time aviation endurance record wasn’t set in an X-plane or other exotic experimental craft. There was no NASA involvement, no high-tech materials or techniques used. It was achieved in the simplest, most plain-Jane general aviation aircraft imaginable. It’s a record that still stands today and might never be broken.

On December 4th 1958, a nondescript Cessna 172 took off from McCarran Field in Las Vegas with two pilots on board. They stayed aloft for more than two months, landing back at McCarran on February 7, 1959.

I’m ready to get out of a Skyhawk after about sixty-five minutes. These guys were flying for sixty-five days! The record attempt was sponsored by the Hacienda Hotel, which today is nothing but a memory, having been imploded and replaced by the Mandalay Bay resort. But that little Skyhawk is still here. It hangs from the ceiling in the baggage claim area at McCarran International Airport, and I’d bet less than one in a thousand who walk by it are aware that it stayed in the air longer than any other manned vehicle in the universe except a space station. No space shuttle or Apollo moon shot ever came close to touching that little Cessna’s record.

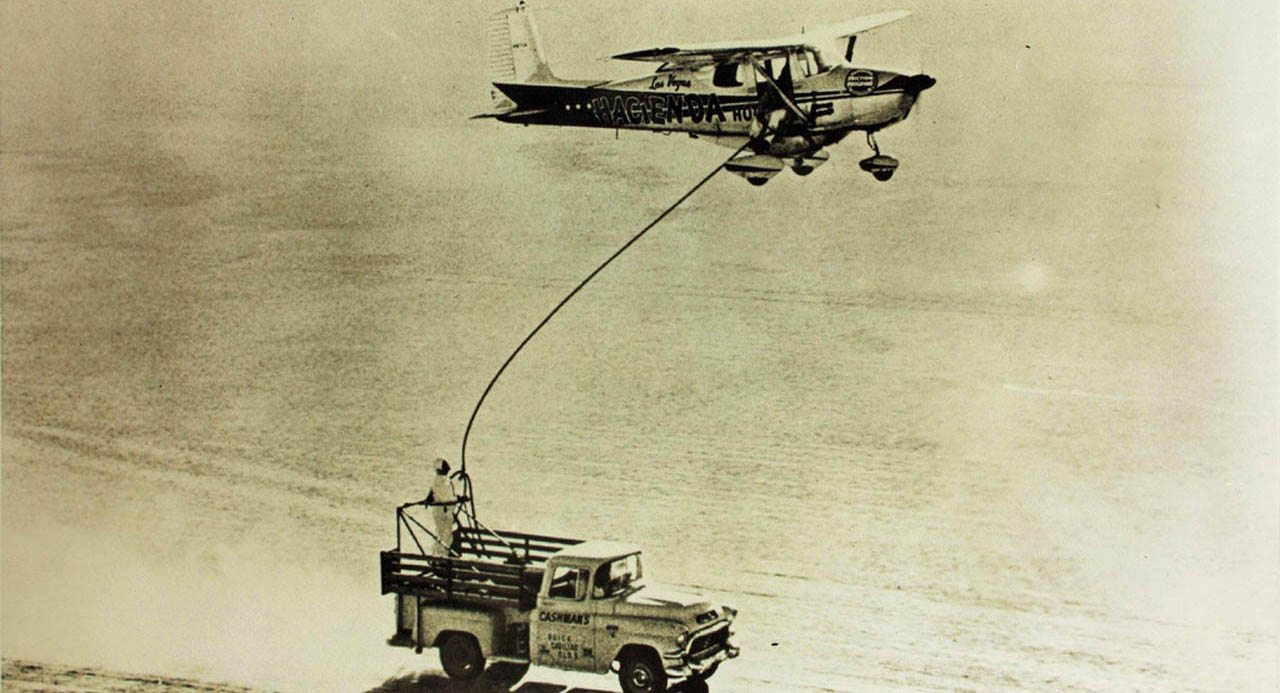

The flying itself was probably some of the most boring you can imagine. Pilots Bob Timm and John Cook spent most of their time flying circuits around Yuma and Blythe. Refueling, as well as the transfer of food and supplies, was accomplished by rendezvousing with a moving car or truck along an open stretch of highway. If you’ve ever been out there, there’s not much to see beyond an endless expanse of the prototypical southwestern desert.

The real story here is, as always, the human one. How do two people live in a loud, vibrating contraption for such a long time? No privacy, no quiet, and not much sleep either. The two pilots flew in four-hour shifts, meaning neither of them got more than four hours of sleep at a stretch for more than two months. I’m not sure I could do that in the peace and quiet of my own home, let alone a mid-50s vintage Skyhawk. Aircraft of that era had great useful loads, but they weren’t exactly known for their plush amenities or soundproofing.

Time was taking a toll on the men and equipment. On January 23 they broke the existing record. They had accomplished their goal but decided to keep flying for as long as they could to protect the record they had worked so hard to capture.

“We had lost the generator, tachometer, autopilot, cabin heater, landing and taxi lights, belly tank fuel gauge, electrical fuel pump, and winch,†Cook wrote.

The spark plugs and engine combustion chambers were loading up with so much carbon by the beginning of February that the reduced engine power made climbing with a full load of fuel difficult.

This is very typical of aviation — the workload rises just as fatigue is diminishing the pilot’s capabilities. Their exhaustion must have been overwhelming after a month and a half in that torture chamber. And then they lost cabin heat (it was winter, remember) and the autopilot, yet still managed to fly on for another fifteen days. Despite being little more than a wing leveler, the loss of the autopilot must have been particularly difficult, as it would have required someone to have their hands on or near the controls more or less around the clock from that point on.

Can you imagine the logbook entry for this flight? “1500 hours, 128 mid-air refuelings, one landing.” The ground track mileage was sufficient to have flown around the earth seven times. Any way you slice it, this was an impressive feat by a couple of ordinary people, one a slot machine technician and the other an aviation mechanic. Aside from the belly tank and a few minor mods, the aircraft and powerplant were basically stock. One wonders how long it took after they landed before those two could stomach the idea of going back up in the air.

It’s interesting how some record-setting aviators — Lindbergh, for example — become household names while others never catch on. Even among pilots, the names Bob Timm and John Cook probably do not ring a bell. I wish they did, because their 54 year old record is a testament to what can be accomplished with sufficient determination. That’s something we could all use a little more of, don’t you think?

This entry is part of an ongoing collaborative writing project entitled “Blogging in Formation”.

Ron,

Fantastic piece! I vaguely remember seeing an image of that airplane refueling, but little else. I had no idea how incredible their accomplishment was, nor did I know the pilots names. Like Jerry Mock there seems to be a hole in the universe for such record-setters, I’m not sure why. Maybe in the 1950s and 60s only rocket-power could capture the attention of Americans. Thank you for letting us celebrate their victor on your website 55 years later.

Brent

You might be right, Brent. Compared with the roar of a Redstone rocket, a Skyhawk puttering along in circles probably didn’t capture public’s imagination. It certainly didn’t fit into the era’s prevailing view of the sleek, high-tech future (think: Tomorrowland). If only they had known that 55 years later we’d still be flying the exact. same. thing…

Wow. Ive always known about the little Cessna in the baggage claim area in KLAS and I’ve given it a nod each time I walk by. What I didn’t know was the time aloft! I thought it was two days, not two months. I had NO idea that any man would be put through so much.

What I WILL nod my head to is Rutan’s Voyager. I had the pleasure of seeing the craft up close at IAD last month. I remember, as a 6 year old, coming down the stairs at home and turning on the TV one Saturday or Sunday morning early to watch Yeager come in for a landing on the Voyager. I remembered how each landing gear came out – one – at – a – time. Nine days aloft on one tank IS testament to no one else but Rutan who made it happen with Huge High aspect ratio wings. That feat was remarkable for a tank of gas.

I can see how Tim and Cooks name didn’t catch on. “flying around blythe and Yuma” with the desert as an emergency landing field inst that daring or risky (unless you might ask a Dr or an Audiologist!). Flying in the blind across the Atlantic SOLO 30 years prior is another story.

An excellent nod to another set of unsung aviation heroes! Looking back on this week’s Blogging in Formation posts, you’re exactly right: it’s about the humans, not the machines. Even my piece, about Filipina pilot hero Captain Grace Baloyo, is about her heroic deed–the fact that she did it in a plane is secondary…

I’ve regularly flown in and out of LAS, and have stopped to peruse the display several times, but even so the insane length of time they spent aloft was so hard to wrap one’s brain around, that I could never remember just how long they actually spent in the air! I can’t even begin to imagine being cooped up for that long!

Great end cap for a great Blogging in Formation week!

Thanks, Eric! I neglected to mention your post about Captain Bayolo… but you’re right, that’s another example.

I too had heard the story if the Hacienda Skyhawk’s record-breaking flight before, but was unable to wrap my head around the idea that a 172 could possible have stayed aloft for more than two months straight. It’s quite inconceivable. The mind almost rejects it as an utter impossibility. I think that’s what makes it so impressive: even knowing the hard cold facts, the brain still can’t accept it.

Makes me wonder if they went on to get their ATPs after that flight. They officially had the time for it at that point!

This is, of course, assuming there WAS an ATP certificate at that time, and that the hour requirements were the same… maybe I’ll make an attempt like that as well, and then start applying to fly the big iron! If I can stomach the thought of another airplane afterward, as you so wisely point out… 😉

Tailwinds,

Andrew

I know you were joking, but it got me thinking: in an era of 24/7 news coverage, the media is always hungry for something fresh to latch on to, so perhaps an endurance attempt would have a chance at capturing the public’s imagination. A turbodiesel powerplant might avoid the carbon fouling issues they had in 1959, and we certainly have better autopilots today, so if the living situation could be made comfortable enough…

Ron, This is a great post! I never knew why that Cessna hung above the millions of people who walked past yearly. What a great story. Your passion for endurance is no wonder. Endurance… pushing yourself harder than you thought you could go, farther than you ever believed, and not giving up no matter what…. is all about the human spirit. That magical power we all have within, but only a few will test. Thanks for a great post!

Thanks Karlene! Pushing harder and further than you ever thought possible is a good parallel for learning to fly, isn’t it? Many barriers and challenges along the way on that journey too. Some are successful and others are not; I think a big part of it is that internal drive, that determination to reach the goal no matter what.

Oh… I completely agree. And gives the pilot training to be stronger, better and wiser in every way. Never give up the great lessons of a good training program. And…this give me a great idea for a new post.

Excellent! I love it when a post of mine inspires someone with an idea. I actually get a lot of my ideas from other things I’ve read. Sometimes a comment on a post gets so lengthy that I cut-and-paste it into a full entry.

P.S. Don’t forget to thank your good friend Ron in the post for the inspiration! (just kidding…)

Always!!! And of course!