Do you ever get the feeling that you were born in the wrong era? I do. It’s ironic because I have a natural affinity for computerized devices, web development, coding, glass panel avionics, and other high-tech elements. Nevertheless, they don’t hold a candle to the mechanical brilliance and timeless design ethos of vintage aircraft. I love ’em.

A student of mine owns a fully-restored 1928 Travel Air 4000, an aircraft that turned heads 85 years ago and still does the same thing today wherever it goes. For all the advances we’ve made since the Roaring 20s, I sincerely doubt my automobile, cell phone, computer, furniture, or other belongings will be around in the year 2098, let alone looking as good as this “old” airplane.

A Travel Air Primer

Even if you’re unfamiliar with the Travel Air Manufacturing Company name, you might recognize people who founded it in 1925: Clyde Cessna, Walter Beech, and Lloyd Stearman. Travel Air was one of the companies that first put Wichita on the map as the “Air Capital of the World”. The firm only lasted a few years, building about 1,800 biplanes before the company was absorbed by the Curtiss-Wright Corporation (which still exists) in 1929.

Among antique biplanes, the ubiquitous Boeing Stearman represents the bulk of the existing fleet — no surprise given that about 10,000 of them were built. Waco biplanes are less common, although they have the advantage of being in active production. If you’ve got the wherewithal (ie. $500,000 or so), a new Waco YMF-5 can be yours. There’s one at John Wayne Airport with a full IFR-certified Garmin avionics suite. Imagine it: a 1930’s tube-and-fabric biplane with a 21st century WAAS-approach capable panel.

Anyway, a Travel Air — one that actually flies, at least — is rare. Relatively few were built, and those that were manufactured were rolled out in an era when preserving aircraft wasn’t as much of a priority. Aviation was fairly new and all eyes were on the future. The past… well, there wasn’t much of a “history” to really worry about. In addition, after the first World War there were plenty of used Curtiss JN-4 and JN-6 series “Jenny” biplanes to be had at a fraction of the $6,000 price Travel Air wanted for their product.

By the time World War II ended, there were tens of thousands of trained and experienced pilots, aircraft were being sold off as cheap surplus, and biplanes made ideal cropdusters, trainers, and personal airplanes. So the Stearman seems to have fared better in terms of survival. You’ll even see the effect on other biplanes, as many Travel Airs have had their landing gear and powerplants converted to the Stearman equivalent because those parts are in better supply.

Today, the FAA has 248 Travel Airs in their active registry, but I doubt anywhere near that many are in airworthy condition. This aircraft was built just about in the middle of the Travel Air’s production run: it’s number 849 and the surviving documentation goes all the way back to the day it was manufactured. The bill of sale was signed by Walter Beech.

The Travel Air has some interesting design characteristics. Like the Waco, Travel Airs were three-place aircraft: two seats in the front and one in the back. The airplane’s landing gear was especially rugged for the day, being built with large tires and strong rubber shock cords on the main landing gear. The wing itself is a historic artifact as well, featuring an undercambered shape. This was common at the time but went out of style pretty quickly thereafter. Also, the Travel Air airframe was designed to allow for different wing designs to be attached. I’m not sure if this was a marketing idea or a cost-saving one.

Flying History

We launched early in the day for some pattern work. His three-point and wheel landings were quite good, so I threw a curve at my student by heading to a much narrower runway where there wouldn’t be as many sight cues to work with. Narrow runways also encourage rounding out too low because of a visual illusion which leads the pilot to believe he’s higher above the ground that he actually is. Result? Bounced landings and some difficulty determining where the edges of the pavement are. But those are mistakes you only make a few times before the proper sight pictures are committed to memory and things fall into place.

After that, we spent some time on wingovers, stalls, steep turns, and teaching techniques in a local practice area before departing on a tour of the L.A. basin. My student is in the process of establishing a sightseeing business with the Travel Air, and we’d been thinking about some routes he could fly which would cater to the Travel Air’s strengths. SkyThrills already does this with great success using one of the “new” Waco YMF-5 biplanes, although they’ve really gone the extra mile in achieving a Part 135 charter certificate with the airplane.

Our basin tour started with an inspection of the Santa Ana mountains while enroute to Dana Point, whereupon we descended to 1,000 feet before proceeding up the coast toward Long Beach and the Queen Mary. Then we made some Class D airspace transitions through Long Beach, Los Alamitos, and Fullerton enroute to a smooth landing at Chino. After a few days of gusty Santa Ana winds and the accompanying crystal clear skies, the prototypical Southern California haze was just starting to return. Catalina and San Clemente Islands were clearly beckoned in the distance. If only this biplane had amphibious floats…

Aircraft like the Travel Air are extremely weather-dependent, even by aviation standards. It’s a flying convertible, albeit one that moves at 100 mph. That’s a pivotal part of the experience — you feel every change of temperature or humidity, you breathe unfiltered air, and the roar of the exhaust stack is so close you can literally reach out and touch it. At night, those metal tubes glow with a hot flame which extends out the back of the pipe. On a good weather day it’s a glorious experience. If it’s cold and rainy? Not so much.

Just the act of getting into the front seat of the Travel Air is an event. For one thing, it’s got a 15 inch tall mini-door which swings out in gallant style. Once you’re in the front cockpit, the leather-wrapped bench seat is wide enough for two but has only a single, extra wide seatbelt without a shoulder harness. Keep in mind, I’m used to having a 5-point harness in the Gulfstream, airbags in the Diamond, and a beefy, secondary lap belt in aerobatic airplanes with a parachute on top of it all. In other words, yeah, I was strapped in safely — by 1928 standards.

My student was kind enough to play passenger for a few minutes while I made a few circuits. I’ve never been a fan of flying from the front cockpit. I do it all the time, but it’s not ideal, because in many tandem airplanes the front hole is more-or-less co-located with the center of gravity, so it’s hard to feel the yawing motion. You’re sitting closer to the engine, so it’s considerably louder. And in this particular aircraft, the front cockpit also lacks brakes, push-to-talk, and instruments.

I can see a modern pilot moaning about the lack of a stall warning horn, angle-of-attack indicator, or GPS. Grrr — don’t get me started.

I’m used to flying with very limited instrumentation while instructing, but this airplane has absolutely nothing up front beyond a stick, rudder pedals, and throttle. Not even an airspeed indicator or altimeter. I had a paper chart, too — but it wasn’t sepia toned or black-and-white, so no style points for that!

Of course, gauges are not necessary to fly. I didn’t even miss them, really. I’d make an occasional query with my student about altitude or airspeed, but for the most part you can judge altitude by looking at the ground and airspeed by wind noise. Close enough for government work, as they say. But it was weird having a huge, beautiful wood panel in front of me containing absolutely nothing. When I first climbed into this airplane a few years ago, I giggled about it for a second and then asked my student if he could check me out on the front seat instruments before we cranked up. He got all the way out of his seat before realizing that I’d pulled a fast one on him.

As is becoming my custom, I hauled out the iPhone 5 every so often and came up with a few photos which I trust you’ll enjoy.

Ron,

1st I’m green with envy. That fact that you get to galavant around in such a classic steed is something I could only dream of.

2nd I’m not sure which is better, your excellent prose or the beautiful images you created (with your phone no less).

Good show my friend!

Brent

Thanks Brent! I get jealous of your RV-8 adventures — and as I recall, you used to test fly a P-51D Mustang replica — so I guess we’re even. 🙂

The trick with the iPhone pictures is mastering the camera’s macro mode, and editing the pictures with Snapseed (which I think is available for both iOS and Android). I never really gave smartphone photography much thought until I read a professional photographer’s opinion that “the best camera is the one you have with you”. The phone’s always nearby, so I gave it a shot and have been fairly happy with the results. I also love how the iPhone automatically organizes the pictures based on date and location, so it’s easy to find whatever I’m looking for.

Yep, I guess we’re even. Alas, so many airplanes and so little time. I narrowly missed a Stearman ride a couple of weeks ago, but I did get a raincheck.

I was just on YouTube looking at videos of other folks who built that Mustang kit (FEW P-51), it sure brought back some memories. I think the way it sounded was the best part.

I’m a huge iPhone fan so I swiftly downloaded that app – very capable and easy to use. Thanks for the tip!

Brent

WOW! What an amazing machine. If he ever does start selling rides, tell him to sign me up. Its true when they say “they don’t make them like they used to” Looks like a lot of time and effort went into building this machine. Heck, its still around and flying today.

As for the Iphotography, you actually very clearly captured my Wife’s house. (I can make our her window) while you were flying over the queen. Do that on a phone with all that vibration I can only imagine a 1920’s Aircraft has…incredible..

Millions of homes in the L.A. basin and I managed to take a picture of your wife’s place. What are the odds?

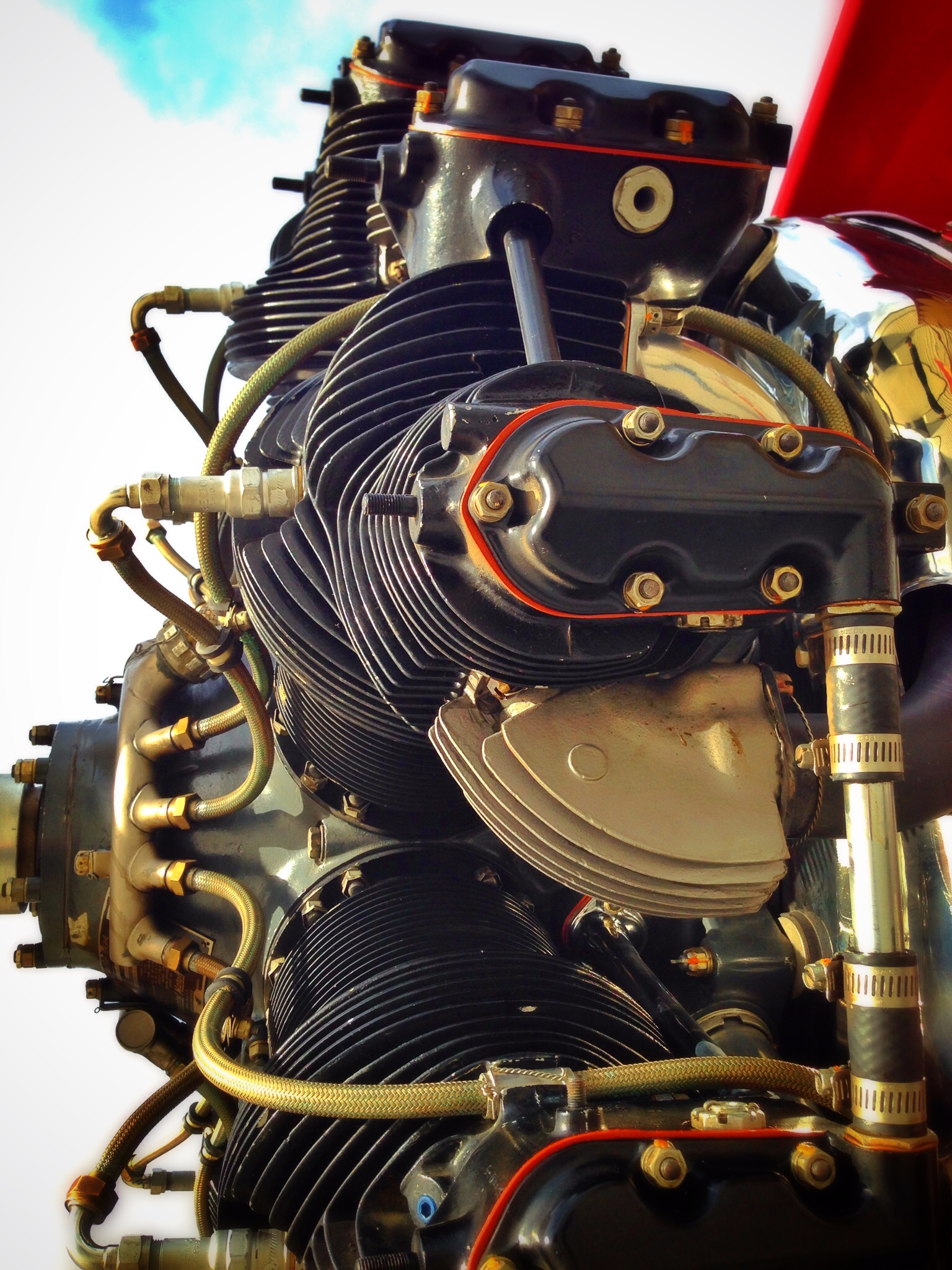

The vibration isn’t bad at all — no worse than any other reciprocating GA aircraft. A fair bit better, actually, probably because of the lightweight wood prop and the fact that it has seven cylinders rather than the typical four you’d find in a horizontally opposed powerplant. The vibration that can be felt is almost welcome — a perfect compliment to the sound of the radial engine.

Yes, a tremendous amount of time went into crafting the Travel Air. That’s one of the reasons they stopped making them. Riveted metal construction was not only more durable, but also faster to build. A lot of time and effort also goes into maintenance on these airplanes, although they’re comparatively reliable because of their simplicity. No turbos, injectors, oleos, flaps, electric motors, computers, etc. Beyond a small windshield, there aren’t even any windows or doors to speak of. Mainly it’s just engine maintenance and keeping the oil and dirt off the fabric skin.

Ha ha. Soon in January I’ll move in with her. Thanks sir

what a gorgeous shot of the engine! lovely aircraft as well.

Glad you enjoyed the photos, Lindsay. Yes, it’s an airplane with countless details. I could have spent all day exploring the little-noticed bits.

Love this! Totally, totally awesome

As much as I enjoy the capability and features of glass airplanes and big jets, to me the word “flying” will always be encapsulated by stuff like this. Glad to know so many others feel the same way. 🙂

I would love to get my pilot’s license one day and own an antique aircraft. You make a great point about how after WWII there were a lot of trained pilots that still wanted to fly after the war, so they found surplus planes for sale. I bet it would be a thrill to fly a biplane from that era. I’ll have to look into training programs so I can get my license first. Thanks for your article.