Early on in my initial flight training, I started hearing occasional references to a requirement for a couple of solo “cross-country” flights. Nobody actually defined the term for me, and this was in the years before the partnership between Google and your ordinary smart phone made figuring these things out a non-event, so in my mind I was looking forward to the adventure of flying literally across the entire U.S. and seeing it all from the air.

I was half relieved, half disappointed to find out that for the purposes of obtaining a my private pilot certificate, “cross country” meant landing at an airport at least 50 nautical miles away from my departure point. Fifty miles? In an airplane? Now how long could that possibly take, I wondered? As it turns out, between the flight planning, pre-flight, taxi time, run-up checks, and just being a slow-moving neophyte, it could take quite a while.

The 50 nm standard also applied to instrument rating and commercial pilot certificate. The ATP certificate was even less restrictive: logging “cross country” time didn’t even require a landing. And last but not least, the general definition of the term in 14 CFR 61.1(b)(3)(i) only required landing in a different place, regardless of distance. You could takeoff from John Wayne Airport and land at Tustin MCAS two miles away and it qualified as “cross country”. What kind of crazy world was this?

The vaunted cross country flight of my dreams would have to wait a while.

Eventually I did start flying across the entire country, and over the years I’ve done it in a wide variety of aircraft ranging from single engine recips down low to the Gulfstream up at FL450. Off the top of my head, I’ve made the trip in a Skylane, Tiger, Cirrus (3x), Pitts, Diamond Star, and Gulfstream. I even did the mid-20s in an unpressurized King Air while sucking on oxygen. Each has it’s pros and cons.

In a more modest aircraft, the trip is always different because of varying weather, even when flying the same general route. You see and feel more of the land when you’re down there. In a jet, it’s the exact opposite. The transcon flights always feel the same, regardless of route or direction. You’re up high, way above the weather, and can’t see much detail. Of course, that’s a welcome trade-off for the ability to climb through ice, clouds, and bumps to smooth clear air on top while making the entire flight in a few short hours.

A couple of weeks ago I made a memorable cross-country once again, bringing a newly purchased 2007 DA-40 DiamondStar to Southern California from upstate New York. And as always, the least pleasant part of the trip was that spent on the airliner. After a full day of work on Thursday, we began with a rush-hour drive to LAX and a jam-packed red-eye to JFK, arriving at 5 a.m. We grabbed a rental car and drove up to White Plains for a pre-purchase inspection and test flight with the soon-to-be ex-owner.

It’s places like White Plains that make me appreciate the weather we’re blessed with in Southern California. We can fly any time of the year in jeans and a t-shirt with little worry about ice, thunderstorms, or whether the very act of starting the engine will damage it unless you carefully pre-heat first. In New York, many folks just put the airplane in a hangar and walk away for six months. Sure, you can fly, but it’s not exactly fun.

It was bitterly cold and windy in White Plains, as it always seems to be when I’m there. Winds gusting to nearly 30 knots. The simple act of opening the canopy is a challenge in those conditions. The DA-40 front and rear canopies become sails, and if you’re not careful the wind will rip them right out of your hand, snapping them up with sufficient force to damage the hinges. Even with three layers of clothing, a jacket, hat, and gloves, my limbs were frozen solid by the time we walked across the ramp to take our first look at the aircraft.

But the inspection and test flight went well and the logbooks were in order, so money and title were exchanged and we departed mid-day for Morristown, NJ to get some paperwork notarized. Here’s a little know fact: many FBOs have a notary on staff. Who would have thought?

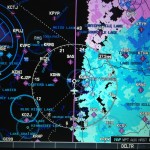

By this time, I was already a bit tired, but weather was bearing down on us from the Midwest. This has been a crazy year for winter weather. A few days before we flew out to New York, a solid line of storms extending from the Gulf of Mexico well into Canada would have made the trip impossible in a DA-40. It literally bisected the country. The 24 and 36 hour prog charts predicted similar chaos descending on the New England area, powered by a collision of unusually cold polar air and warm moisture from the Gulf. Bad juju.

Our strategy was simple: fly VFR. If we can see the weather, we can avoid it. This is something they don’t often tell you when you’re spending all that money pursuing an instrument rating. In a light aircraft, sometimes VFR is safer. The DiamondStar has no de-ice capability, so if the clouds are below freezing, you can either stay out of them or, if that’s not safely possible, remain on the ground.

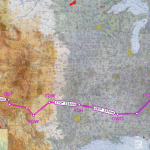

Anyway, our trip to the west started off with the compass pointing south. Past Washington D.C. and the infamous ADIZ, tracing the Appalachians and we skirted the eastern edge of a band of mixed rain, ice, and snow. The DA-40 had an active XM weather subscription, so we were able to see the big weather picture as we flew. It was a good thing, too, because headwinds kept our ground speed in the 80-90 knot range for most of the trip.

I’m a big fan of the DiamondStar, but one “gotcha” with this aircraft is the low Vno speed: 129 knots. At low altitudes, the airplane will cruise in the yellow arc, so any turbulence requires an airspeed reduction. Once you’re above 6,000 feet or so, the indicated airspeed gets low enough that full-throttle cruise will be below that Vno limitation.

I made the trip with a talented automotive engineer and designer named David who, while he’s not the owner of the plane, is going to be the primary pilot. He’d never flown east of Palm Springs, so this was a big deal! I’m actually glad the weather was a challenge, because it presented a much more valuable learning opportunity for him. Between our low altitude, the (relatively) high terrain of the Appalachian range, and the wind, we spent the first four or five hours fighting some annoying up- and downdrafts. Or should I say, he did. After ensuring the path ahead was clear, I took a nap!

The first fuel stop was a night landing at Lewisburg, West Virginia where somehow it was even colder than in White Plains. A quick bathroom break and we were in the air again, finally in clear skies on a direct route to our overnight destination of Knoxville, TN. I should point out that when we left New York, we had no defined route and no hotel reservations. Where we went and where stopped for the night was going to be dictated by weather. There are plenty of airports all over the country. Rarely is one far away. If either of us didn’t like what was ahead or just wanted to stop, we’d stop. And our plan did change several times based on what we were seeing. Even fuel stops were fluid, as the strong winds decreased our range.

Day two was much easier. The weather kept us heading southwest until we passed Birmingham, Alabama but was relatively good during our fuel stops in Greenwood, MS and Ada, OK. Greenwood is an interesting place. It’s got a huge new control tower and scads of old airliners on the ramp, but curiously, no traffic. Even the tower controller seemed to be half-asleep.

The FBO manager, quite a character in his own right, told us the tower was the result of military activity. They use the airport for practice approaches. The airliners were old lease returns that GE Capital was storing or parting out. I asked why they’d part out airliners that looked relatively new and he replied that some of them were just odd cases, like a 7,000 hour 747 that had a container of mercury spilled inside. Apparently the cleanup costs made salvaging the airframe economically unfeasible.

We ended the day at Tradewinds Airport in Amarillo, TX because David had relatives there. His uncle was leaving a couple days later to take this homemade trailer to Florida and bring home a new mast for his 40′ sailboat. I think one of the lessons David learned from the trip is that most of the country is very windy compared to southern California. All that stuff he learned about positioning the controls for crosswinds that seemed so meaningless in Orange County was suddenly important.

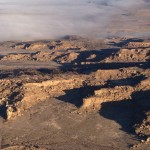

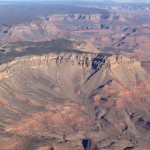

Day three (or four if you want to count airlining) found us ahead of schedule, so we made a detour toward Roswell, NM for some alien beef jerky, a visit to the International UFO Museum and Research Center, and an even larger aircraft boneyard. We had hoped to make it as far as Flagstaff, AZ by the end of the day, but new hazards started to appear in the form of lowering clouds and rising terrain.

The terrain issue out there is interesting. There were no “mountains” per se, just a ground elevation that slowly, inexorably rose toward the heavens. We were at 10,500 MSL yet only 3,000 feet above the flat terrain. The squeeze started to make itself known right about the time the sun was setting. It was raining, we were getting a wee bit of ice, even in clear air, and the thick layer of clouds above was blocking out much of the remaining sunlight. So rather than press on toward a dark night time approach into Flagstaff — which, by the way, is surrounded by mountains as high as 12,700 feet — we diverted to Gallup NM, arriving at our hotel just in time to see the lights go out at Superbowl XLVII.

Our final leg on day four brought clear skies and an actual tailwind (!) as we coasted into Henderson, Nevada where David was due to work out some kinks in a new bus that the company was displaying at the International LCT Show.

It was fascinating to see how these trade shows go together. For one thing, the MGM Grand’s convention center was going to be full of limos, buses, and other massive vehicles. The logistics required just to get every vehicle loaded into the building in the right order was quite significant. Everyone wanted to have their vehicle displayed a certain way, so these behemoths were moving to and fro in a very confined space. I’m amazed there were no collisions.

Even something as simple as hanging the signage for a company’s booth was a big deal. It’s done by union members and therefore the cost of hoisting these relatively small signs can be as much as $3,000.

The trip ended for me in Las Vegas after about 23 hours of flight time and 210 gallons of fuel burned. David stayed at the show and I took the Southwest shuttle back to Orange County. Another coast-to-coast round-trip in the books. If you haven’t done it, I highly recommend “low and slow” as a great way to see the country, as long as you’re up to the challenge of course. A few tips:

- Be flexible.

Don’t get attached to any particular route, airport, or schedule. It’s amazing how many solutions make themselves known once you do this. - Use CRM.

“Cockpit resource management” doesn’t just mean another pilot. It includes ATC, XM weather, your iPad, and whatever else is available. - Don’t forget about VFR.

Sometimes that makes a trip more flyable, not less. - Manage your risk.

Especially if you’re new at traversing long distances, tall mountains, unfamiliar airspace, and weather. Ask yourself how tired you are, how much experience you have in the aircraft you’re flying, and what tools are available. We had a glass panel, a great autopilot, a satellite datalink, and two pilots on board. - Know when to say when.

If we had been a day later departing New York, we’d have spent several days there waiting out the weather. And that’s fine. Recognizing that light aircraft have limits and that we cannot control the weather is like a 12 step program for pilots. It’s not easy, but we have to do it.

Nothing says “freedom” quite like hopping into an airplane and seeing the States from a couple thousand feet up. As the Southwest ad says, “you’re now free to move about the country”. May that never change.

Here are a few photos from the trip:

Beautiful photographs and what an experience – nothing like low and slow. Your tips you list should definitely be considered by all. The Diamond seems like a lovely aircraft for such a mission except the airspeeds could be a little higher 🙂 Thanks for sharing!

Glad you enjoyed the article. Sorry about the IE9 issues — I tried to replicate it but I am already on to IE10, which doesn’t seem to be affected. Everything posted just fine for me with that browser.

Great write up and photos! But what really caught my attention was your statement that: “Our strategy was simple: fly VFR. If we can see the weather, we can avoid it. This is something they don’t often tell you when you’re spending all that money pursuing an instrument rating.” I’ve been a VFR-only pilot for a decade, having flown many multiple state cross country flights safely, with the weather situation easily assessed visually. Your comment is exactly one of the reasons that I deferred instrument training as long as I did (I’m about halfway through the rating now). It is not a viewpoint that I often see espoused – it’s nice to read some evidence that I may not have been completely crazy all these years.

Hi Chris! You’re definitely not crazy.

I sort of understood why nobody told me about the limitations of an instrument rating back when I was working on mine. Here in southern California, our IMC is quite flyable. Not much in the way of organized thunderstorms or widespread icing, and our IMC is often smooth coastal stratus. But the rest of the country is not so lucky. IFR conditions often have hazards that light GA aircraft cannot safely handle. The Rockies have high terrain. The south has the Gulf moisture. The north and northwest get low freezing levels for much if the year.

That doesn’t mean you can’t fly in IMC, but you have to carefully consider the ancillary conditions. If the MEA is below the freezing level, or there’s good VMC with sufficient terrain clearance below the clouds, or the flight is very short with lots of alternates enroute, you might be plenty safe.

Anyway, I think of IFR and VFR as quite similar: both are tools in a pilot’s arsenal, each having their pros and cons. A smart aviator will make skilled use of both, and have a good sense of when to just stay on the ground.

Well said, Ron. And in my case, I was thinking very specifically about thunderstorms and icing. But I agree, IFR and VFR are both tools and having more tools at your disposal is always a good thing (so I’m glad I finally got going on the rating and feel that it is upping my game as a pilot).