Even with decades of experience and thousands of hours in the cockpit, the opportunity to try something new is never far away when you work in aviation. That’s one of the factors which keeps aviators coming back, the opportunity to learn and grow. So it was not surprising that I added another “first” to my logbook recently when given the opportunity to taxi an airplane through the streets of downtown Palm Springs as part of the annual “Parade of Planes” at the AOPA Summit convention.

The Summit is an annual aviation expo put on by the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association, the largest general aviation organization in the world. Despite AOPA’s large size — they claim more than 400,000 members — the size of the event is nowhere near as large as EAA’s AirVenture. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, though. You can easily get overwhelmed at Oshkosh, whereas the AOPA shows tend to be smaller and more manageable.

Anyway, AOPA Summit alternates between the west and east coasts. Palm Springs has proven to be an ideal location for the west coast event for several reasons, not the least of which is the close proximity of the airport to a beautiful new convention center. The powers that be in Palm Springs simply close a few streets for a couple of hours and voila! A long taxiway is created direct to the site of the convention. You can see the 5g Super Decathlon taxiing along the street in this video.

Palm Springs is famous for golf courses, resorts, and spas, but even more important for pilots, it also has the advantages of good weather and a network of local reliever airports. For those stuck on the ground, the city is easily accessed from major metropolitan areas. San Diego, Los Angeles, Orange County, Las Vegas, Phoenix, and many other locales are just a short drive away.

I’d been to two previous AOPA conventions as a visitor, but this was my first time as an exhibitor. A colleague recently started an American Champion Aircraft sales dealership and I was in Palm Springs to represent his company and sell a few airplanes. He had just taken delivery of a new fire engine red Super Decathlon to use as a sales demonstrator, and that was the plane we had there at the show.

It was interesting sitting on a city street with the airplane. Normally that sort of thing would bring out the authorities with sirens and lights blaring, but we were in good company with about 50 other aircraft surrounding the convention center as well. Speaking of which, I was pleased to see that about a dozen of the planes were tailwheels. I counted three Waco YMF-5s, two Aviat Huskies, an RV-8, a Carbon Cub, a Corsair, a Bearcat, a Bigfoot, a C-195, a couple of Kitfoxes, a Glasair Sportsman, and at least a few others I’ve forgotten about.

Meanwhile, Cessna was completely absent from the show. How’s that for a reversal? Ten years ago you would have seen a huge display from Independence and virtually no tailwheel airplanes.

American Champion’s line of products is quite interesting. Some of them don’t really have any competition in the marketplace at all. The Decathlon is a good example. At first look it seems the Cub, Husky, and Maule would be direct competitors, but none of them are built for aerobatics. In fact, there are no other certificated aerobatic trainers being produced right now. The Decathlon not only serves that market, but also functions as a roomy and comfortable traveling aircraft with plenty of cargo space.

The Super D’s good visibility and short field performance even make it a respectable back country platform. It’d also fit right in towing banners, functioning as a primary and/or tailwheel training aircraft, or appearing in the lower levels of aerobatic competition. Even if the airplane is never used for aerobatics, the +6/-5g load limit certainly inspires confidence in the Decathlon’s structural integrity.

And ACA is constantly improving the airplane. Over the past few years the airplane has gained metal wing spars, aluminum gear legs with internal brake lines, modern avionics, exterior LED lighting, and a wide variety of high performance composite propellers.

The latest iteration of the airplane is the Xtreme Decathlon, which includes a 210 hp engine, a new wide-chord prop, redesigned ailerons, shorter wings with squared-off wingtips, a better cowling, and — most exciting of all — I understand they’re pursuing IFR certification for the airplane. In addition to everything else, the Decathlon will be able to function as an IFR trainer and give sufficient instrument flying capability to allow passage through the coastal stratus often present along the west coast.

I know, I know: an aerobatic taildragger with IFR certification? It may sound sacrilegious, but at the AOPA Summit there were three huge open cockpit Waco YMF-5 biplanes with more glass panel instrumentation than you’ll find in any Cirrus. Like it or not, this is the wave of the future and it’s enveloping everything that flies. Anyway, suffice it to say there’s a lot of excitement over the Decathlon for what it can do, and what they’re making it capable of doing at the factory in Wisconsin.

Another interesting offering from ACA is the original Champ. Designed in the early 1940s, not many people at the show were aware that the Champ is Sport Pilot-compliant and is still being produced by American Champion. Talk about a classic and timeless design! The Champ was the progenitor of so many classic airplanes, including the the Citabria, Scout, and Decathlon.

Anyway, after spending three days at the convention, I’m starting to get a picture of what the world of light GA flying will look like in the years to come. It’s in vogue to say that general aviation is dying off; I’ve even lamented the decline in activity myself. While it’s true that things are unlikely to return to the heyday of the late 1970s when it comes to sheer numbers of aircraft being produced by the big airframe manufacturers, it seems clear that market forces are driving the GA world toward the kit-built airplanes and the refurb/retrofit market for existing airframes.

The total number of RVs being constructed each year is approaching that of the entire certificated factory-built industry. Reason? You simply get more for your money. Way more, in fact. Maintenance and operating costs are lower. Best of all, you gain additional freedom — the reason many of us got into aviation in the first place — not available to certificated aircraft owners.

I had one guy at the Summit regale me with a 20 minute tale about how difficult it was to obtain a battery for his Champ. Even the factory wouldn’t sell him one because of some obscure FAA approval which didn’t apply to his serial number because it was built before they started putting electrical systems into those airplanes. The fact that they’re building the same airplanes now with an electrical system using that exact battery apparently meant nothing.

The homebuilt trend extends pretty far up the food chain, too, with companies like Epic and Lancair producing pressurized turbine airplane kits meant for serious high-speed, high-altitude travel.

The other emerging trend — one that will undoubtedly continue over the long term — was that of rebuilding and retrofitting older airframes with new technology. Engines, avionics, interiors, lighting, entertainment systems, airframe upgrades, etc. There were a surprising number of turbine and diesel engine conversions on display in Palm Springs. Bonanzas, Skylanes, Centurions, Caravans, Skywagons, and even a C-340 with Rolls Royce 250 engines.

Turbine conversions make particularly good sense as an upgrade for pressurized piston twins today, because high prices for fuel, parts, and the questionable future of leaded avgas has many twin owners headed for the exit. Instead of two finicky and maxed-out piston engines, drop in a pair of highly de-rated turboprops and you’ve got a whole new airplane. Expensive, sure, but the reliability, ease of operation, and long TBO of those powerplants should serve the cabin class twin fleet very well for decades to come.

Advances in airframe design are still occurring, but not at a sufficient pace to warrant the high price required by the OEMs. There will still be sales of new aircraft, but I would not expect the pace to return to the “good old days” — even if your definition of that term only goes back to the 1990s.

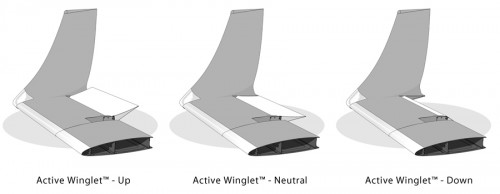

Speaking of airframes, I was intrigued by a new modification for the Cirrus from Tamarack Aerospace Group which adds winglets to the SR22. Winglets are not new technology, but the way Tamarack has gone about tackling the certification challenge certainly is innovative. They’ve adopted a design that incorporates a control surface on the horizontal portion of the winglet. It’s like an aileron, except both winglets’ control surfaces are automated and move in tandem.

The purpose of the control surface it is to aerodynamically “cancel” the added lift provided by the winglet during high load conditions, thereby moving the wing’s center of lift back to it’s original design location during turbulence. The only alternative to the “active winglet” method would be to re-certify the wing for the full range of load factors with the center of lift in a different location. That would be expensive enough on a single type of airplane, especially if the wing were found to need further modification to withstand the added stress.

Winglets are an ideal modification for nearly any airplane, as they improve efficiency and reduce fuel consumption, but this one comes with considerable added complexity. Instead of two control surfaces on each wing there will now be three. The system has only one electrical circuit, meaning any failure of the active winglet electronics will reduce the Cirrus’s maximum allowable speed to 120 knots indicated. In addition, there’s always the possibility of a “split” or even a physical jam of the control surface which would impart a rolling moment.

If the active winglet gets FAA approval, in theory winglets could be added to virtually any fixed-wing aircraft with minimal certification hassle. And that’s really what stops innovative ideas from coming to market: the cost — both in time and money — of getting the nod from the Feds. As the market gets smaller, the stifling effect of certification requirements will only continue to grow. I believe even the FAA would agree with this, as they’ve recently announced a goal of reducing the burden of certifying new products.

It will be interesting to see what kind of reception Tamarack will receive from the Cirrus community. They are, to a large degree, eager adopters of advanced technology: composites, glass avionics, airframe parachutes, side sticks, balanced fuel injectors, lean-of-peak operation, etc. But in these austere times, will that reputation remain intact? The list price for Tamarack’s SR22 winglet installation is $60,000.

Finally, I’d be remiss in not taking note of the ever decreasing cost of those glass panels. It wasn’t long ago that a Garmin G1000 added $50,000 to the cost of an airframe. In Palm Springs, the Dynon SkyView was on display for about 1/5th the price. To be sure, the Dynon is not an FAA-certified avionics suite, but it portends a future of better products, stiffer competition, and lower price points for those computerized goodies regardless of certification status.

Glass may be seen as a luxury rather than a necessity. For airplanes like the Super Decathlon, that’s definitely true. In fact, a few people remarked that the 5g Decathlon was the only airplane they’d seen at the show which didn’t have a GPS. Truth be told, we were sort of proud of that fact. But with the impending requirements of the FAA’s NexGen program, it behooves all of us to stay abreast of what’s coming onto the market. Eventually we will all be beneficiaries (or victims, depending on your point of view) of the relentless march of computer technology into the cockpit.

3 comments for “AOPA Summit”