The life of an aviator is indisputably rich in adventures, unique experiences, and, as Magee phrased it, “a hundred things you have not dreamed of”.

Even in that life, however, there are a few days which stand above the rest. Who can forget their first solo, the successful checkride, or the name of their first passenger? As anyone who’s been there can attest, even the most diminutive among us stands ten feet tall at the end of those flights.

Another big moment — one of the very sweetest in my experience — is the day you escape any niggling notions of common sense and purchase an aircraft of your very own. Today, that often means what a salesmen would refer to as a “pre-loved” aircraft. Pre-owned. You know, used.

A select few among us, however, still have the opportunity to hop a miserable flight in the aluminum tube and take delivery of a brand new airplane just as it rolls off the final assembly line. Think of it! A gleaming aircraft sitting under the lights with flawless paint and interior, the latest technology, zero hours on the Hobbs, and even that elusive “new airplane” smell.

Those who’ve had the experience are typically the deep-pocket types. But occasionally a professional pilot will get to be part of the experience as an instructor or ferry pilot. I’ve had three such opportunities in my career thus far, and even on the periphery of the experience it’s an exciting thing to be part of.

The most recent of the three was a new turbo-normalized X-Edition Cirrus SR-22. The owner purchased the aircraft before he’d even started pilot training. I saw the option list and it literally had every box checked off. In addition to the dual turbochargers and dual intercoolers, it had dual AHRS, dual air data computers, synthetic vision, infrared EVS, G1000 Perspective avionics, oxygen system, TKS “known icing”, an upgraded propeller, and a dozen other things.

I don’t think the buyer thought about the weight of all this stuff when he was selecting his options. The airplane is the heaviest Cirrus I’d ever flown. In fact, the full fuel payload was only sufficient for a single person. I don’t mean a single person beyond the pilot — I’m talking just the pilot! We were over gross weight for the first leg of our return flight, as I’d never even considered the need for a weight and balance computation with just two of us on board. Lesson learned.

We found out later that part of the problem was that this airplane was originally built as a normally aspirated Cirrus. The market for those airplanes was pretty soft at the time, so in order to move the inventory, they retrofitted it with a turbo system at the factory.

This shouldn’t have caused a weight penalty. However, the folks at Tornado Alley Turbo in Ada, Oklahoma took one look under the cowling and realized that this was an older, heavier turbocharger kit that had been in use before the advent of Cirrus’s flight into known-icing (FIKI) certification. The FIKI system has dual pumps and more extensive TKS panel coverage on the airframe, leading to higher weight.

Cirrus had asked Tornado Alley Turbo to find ways to lighten the exhaust system on the FIKI SR-22s, and TAT responded by designing a new exhaust system with lighter material that offset the weight of the deicing components. Problem solved.

The question is, why wasn’t this serial number retrofitted with the light exhaust? TAT surmised that this heavy exhaust system had been sitting on the shelf in Duluth and the Cirrus folks decided to put it on the plane. Good for Cirrus, bad for the new owner of this aircraft, as he may own the heaviest SR-22 in the entire fleet. Although for what it’s worth, I don’t think he really cares one way or the other.

Anyway, I managed to take a few photos along the way, and offer this retrospective on a delivery trip for a brand new airplane.

The airplane had only 13 hours on it when we accepted delivery at the factory in Duluth, MN. Can you imagine the smell of all that sumptuous leather? Thirteen hours is just enough for the production test pilots to ensure everything works properly and the included factory training for the new owner.

Departing Duluth, we cruised in the mid-teens to our first fuel stop in Kansas City. Pit stop, refuel, a quick call to my nephew Michael to say hello, and we were back on the proverbial “road”.

The airplane’s weight was easily felt on takeoff, but once airborne she seemed to do just fine. As with all the heavy turbo-normalized SR-22s, the airplane gave the best numbers up around FL250, where we’d see true airspeeds beyond 200 knots. This was a pretty typical ground speed during our trip. My favorite part of the flight was always the descent, where the ground speed would run up to about 250 knots (288 mph).

The Perspective avionics suite in action. Notice the Garmin GFC700 autopilot. This delivery was about a year ago, and at the time that autopilot was brand new.

The new owner wanted to stop in Ada, OK to have the guys at Tornado Alley ensure the turbo system was set up correctly. As it turns out, no major adjustments were needed, just a few clamps and such needed tweaking.

Our visit to TAT added to my already high level of respect for the company. They had guys working on our plane all afternoon. The final charge? Zero dollars. They were just happy to have us there, the logic being that if the turbo system operated properly, we’d be happy customers and it would help their reputation. I couldn’t agree more.

I think there’s also a bit of a safety concern. These turbochargers and the related exhaust components are high speed (30,000 RPM), high heat producing widgets. An exhaust leak can be a serious hazard, and turbo system maintenance is vital to safe flying. It’s not that they don’t trust Cirrus to set up the turbo properly, but the folks in Duluth couldn’t be as knowledgeable about the turbo as the folks who designed and built those components.

TAT found that this airplane has the older heavyweight turbo system on it. Apparently it was built as a normally aspirated airplane and then turbocharged later in order to sell it. While the guys were working on the plane, they gave us a car to drive into town for lunch, and upon our return offered us a tour of the GAMI/TAT facilities.

This is a mockup of what the turbo system looks like on the SR22. They build it, box it up like this, and send it to Duluth. Cirrus just bolts it to the engine. TAT’s goal was to make the installation as “idiot-proof” as possible.

This is where the balanced fuel injectors — sold under the name GAMIjectors — are manufactured. These balanced fuel injectors are the key to lean-of-peak engine operation and have been a part of the Cirrus since the beginning. I’ve flown a thousand hours behind these things, so it was fascinating to see how they’re made.

These are molds for part of the turbonormalized SR-22 exhaust system.

This is an SR22 turbo system, boxed up and ready for shipment to Duluth.

Exhaust component inventory on the shelves at Tornado Alley. Each of those pieces is worth thousands of dollars.

GAMI has a highly instrumented test cell where they test out all their products. Right now they’re working on the G100 unleaded 100 octane fuel. You can see a tank of the stuff on the trailer in the foreground. At the time of our visit, they were testing it on an SR22 they had put into the Experimental category.

This Continental IO-550-N engine has been running at 400+ horsepower for years, and it was at TBO when they installed it!

The test cell control room. The circuit boards are for an upcoming turbo and fuel controller. At the time of our visit, the buzz surrounded a new feature called World Peace.

We departed Ada late afternoon for our next stop, Albuquerque. While in cruise, an instrument scan of the engine page showed an electrical anomaly.

It seems that the Cirrus’s electrical issues haven’t completely been solved, although they’re a great deal better than they were in the days of the early SR22 models with the “old” electrical system and the analog engine gauge backups.

This is a good learning opportunity. Alt 1 shows no amps, but all bus voltages are normal. What’s happening here?

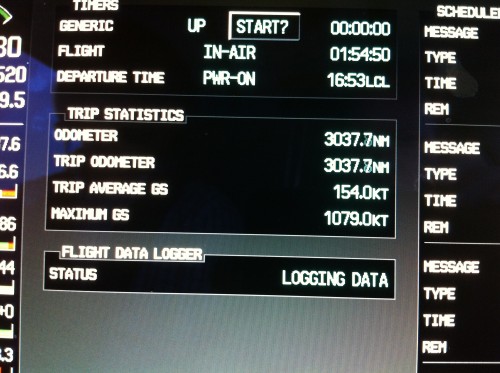

Check out the “max groundspeed” number! Apparently this is not only the heaviest SR-22 in the fleet, but also the fastest…

The next scheduled stop after Albuquerque was Las Vegas, however we elected to continue on to Los Angeles due to weather coming up from the south. As it turns out, it was a good move. We would have been stuck there for days.

This photos shows one of the great safety features of the glass panel. Weather is downloaded from the XM satellite and displayed on the huge MFD map. On the right side of the screen you can see that it’s showing NEXRAD radar, cloud tops, lightning, cell movement, SIGMET/AIRMET, METARs, and PIREPs — all in graphical form, along with the age of the data (typically 2-5 minutes old).

By watching the rate at which the cells were moving from left to right, we were able to time our passage through the “gap” between the blue restricted areas on either side of the Daggett VOR.

Looking back at the weather we had skirted.

The high desert north of Los Angeles. We were passing over Lake Arrowhead and looking west. These isolated buildups are typical of the high desert area in the summer.

Delivery completed! The shiny new airplane is tucked away for the first night in her new hangar at Torrance Airport.

Thanks, Ron. I really enjoyed the story. It brought back a lot of memories.

David

Totally. Every time I make a transcontinental flight I invariably think back to that first one with you back in the day. Good times! I think the westbound trip against those crazy headwinds still ranks as my longest single day of flying.

Hi Ron, nice article. So I’m assuming that since this is all FAA-certified stuff the TAS at high altitudes (high, going downhill fast) isn’t an issue? No flutter issues, right? I’m assuming (hoping!) it has the same airframe and limit envelope as the usual turbo-charged SR22s.

No, it’s not an issue. You’re correct in noting that flutter can be a problem with high altitude, high IAS descents.

However, the turbo -22 has a Vne which varies depending on altitude. At FL250, it’s 170 knots indicated. On a standard day that’s a true airspeed of about 250 knots. Of course, with a tailwind that number can escalate dramatically and give some impressive ground speeds.

Oh nice! So you just fly the IAS, I assume? With all that fancy glass I guess the red arc just moves to where it needs to be. (Or is that now a red bar on an IAS tape?) It sounds like a virtual airliner.

From an avionics and automation standpoint, it sort of IS a virtual airliner. People try to use it that way, which — come to think of it — might help explain the high accident rate of the SRXX series.