Aviation is a fascinating, almost secret world. To those on the outside, it basically consists of airliners and… uh, more airliners, I guess.

When people learn that I’m a professional pilot, they invariably ask which airline I fly for. When I tell them I don’t fly for an airline, they say “ohhh” in that sad empathetic tone reserved for downtrodden, second class citizens.

Little do they know there’s an entire world of flying out there, much of which does not involve an endless series of occupied gates, surly passengers, overcrowded airports, corporate mergers, pay cuts, bankruptcies, and nights spent away from home.

One of the things I’m most frequently asked about by those who dig a little deeper into my flying career is my work for the “Medfly program” here in Southern California. What is it? Why is it needed? And what the heck is a Medfly, anyway?

The short version: the program is a cooperative effort between the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture to control the Mediterranean Fruit Fly population here in the state.

Medflies are not native to the state of California. On the contrary, they are highly destructive to more than 400 varieties of fruits, vegetables, nuts, and other crops. Keep in mind that agriculture is California’s largest industry and California is by far the largest economic engine in the country, and you can understand how these little insects could cause some serious damage. I’ve heard that our program, which costs about $25 million per year, saves more than a billion dollars in crop damage.

In the early 80’s, the Medfly problem even cost the state’s governor his job. Medfly eradication in those days was done with malathion, a controversial pesticide which was sprayed over populated areas by a fleet of helicopters. Then-Governor Jerry Brown claimed the pesticide was not harmful, but the public was skeptical, and at the very least, it damaged the finish on cars left outside during spraying operations.

Rather than run for a third term, Governor Brown ran for U.S. Senate but was defeated by Pete Wilson, in part due to extremely poor public opinion of the way he handled the Medfly outbreak.

Most people who lived in southern California during that period assume I must be spraying malathion, but that practice ended a long time ago. Today, we use a non-pesticide method called the “sterilized insect technique”. Basically, male flies are raised in captivity and irradiated to sterilize them. Then they are released from aircraft, and these sterile males mix with any wild female population. Their attempts to breed are futile, and without any reproductive capability, that generation of flies dies off. The program releases flies in the southern California area as a preventative measure even when there are no major outbreaks.

One of the earliest questions I had about the program was why it was necessary here in the L.A. basin. There’s very little agriculture left in this area due to the high population density. Wouldn’t it be better to drop flies in the San Joaquin Valley where most of the farms are located? I was told that although there’s little agriculture in the Los Angeles basin, there are a lot of immigrants and cargo coming into California via the roads, ships, and airports, and that’s how most of the wild Medflies find their way into our fair state. It’s also why there are agricultural inspection stations on the way into California.

If you’d like to read the California Department of Food & Agriculture’s official explanation of the program, they have a detailed breakdown of how it all works on their web site. Rather than re-hash that, I’ll give you a photographic look at the program from a pilot’s perspective.

By the way, I should note that I don’t work for the CDFA. I work for a company called Dynamic Aviation, which is contracted by CDFA to handle the actual flying. The pilots, mechanics, and aircraft are Dynamic assets. It’s a fascinating company to work for, but I’ll save the company details for a future post.

OK, here we go! The day starts at 4:45 a.m. Yes, you read that right. I get up, take a shower, eat breakfast, make a brown bag lunch, check weather, and head out the door by 6:00 a.m. But when that alarm goes off at 4:45, I always wonder what the hell I’m doing up at that hour.

It used to be a lot harder to work this schedule when I was also singing for Opera Pacific. Every now and then I’d have a rehearsal or performance the night before which wouldn’t allow me to get to bed before midnight at the earliest, and then have to get up at 4:45 the next morning. Ugh.

I don’t have any photos from the next thing, but I arrived on base at about 6:30 a.m. to start the dispatching tasks for the day: checking & printing weather, issuing flight assignments, coordinating with the CDFA personnel, filing flight plans, and basically doing a lot of paperwork. That’s the one constant in aviation: paperwork.

After that, I proceed to the flight line and join the other guys in performing the kind of mundane task you don’t see in Top Gun: washing an aircraft. Everyone pitches in, pilots, mechanics, etc. I don’t mind it, because it’s a chance to watch the sun rise, joke around with the other crews, and stretch out a bit before the 6-7 hours of flying which follow. Hours of sitting in a seat fairly motionless, I might add:

After the wash, the aircraft is towed back to the flight line and the crews start pre-flighting their aircraft. We typically send out four or five aircraft per day. Each aircraft will fly two or three flights totaling five to seven hours of flight time. So that’s 25-35 hours of flying for our fleet each day, and we do it seven days a week.

This is Tim, my first officer for the day, doing the towing duties. Like many of the pilots at Dynamic, Tim is also an A&P mechanic, meaning he can fix the planes as well as break them. I can only break them… but in my defense, I do it very well. 🙂

We operate out of a military base which sits on some prime real estate near the ocean right on the border between L.A. and Orange counties. It’s a “Joint Forces Training Base”, whatever that means. We just call it “Los Alamitos”.

For a military airfield, it has remarkably little flying activity. There are some helicopters based here, and occasionally the President, F-18s, or other aircraft will fly in for a while. Sometimes a civilian 737 will fly in to drop of soldiers returning from Iraq or Afghanistan. During the annual fire season, military Blackhawks are sometimes pressed into service to fight the fires.

But for the most part, we are the main users of the base’s runways. In 800 hours of flying off this air base, I’ve yet to see another non-Dynamic aircraft taxiing at the same time as me anywhere on the airfield.

Here’s a pair of T-45A Goshawk jets near the wash rack:

Within about 15 minutes, our aircraft is prepared for departure. Fuel and oil checked, chocks and covers removed, dispersal equipment checked, cockpit setup complete, and we’re hooked up to an external generator to keep the refrigeration equipment cold. The flies are kept at about 40 degrees so that they don’t try to escape from the box. At this point, we’re just waiting for the CDFA personnel to arrive with our cargo.

You’ll notice the interior has been stripped out of this aircraft. These airplanes are ex-military U-21A turboprops — basically an unpressurized King Air 90. The passenger seats are replaced with a refrigeration and auger system used to distribute the flies. We also have upgraded avionics, wig-wag landing lights, traffic detection systems, and other modifications.

The “Restricted” placard indicates that this aircraft is certified in the Restricted category (due to our installing non-aviation equipment) and cannot be used to carry passengers or non-essential personnel.

In these photos we have the cargo door open and are waiting for our load. Notice the fly chutes hanging down from the belly of the aircraft in the second photo. Also, note the power cord which is providing electricity to the refrigeration unit.

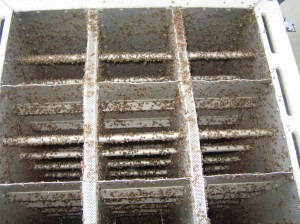

Here the CDFA guys have arrived with our box. This thing contains several million flies. The sterilized ones we drop have an orange dye on them for ease of identification when they show up in the little fly traps placed around Southern California. We load the box, fill out some paperwork to confirm the load weight and the regions we’re headed to, as well as an ETA for our second flight, close the door, run some checklists, and off we go!

According to my watch in the photo below, it’s about 9:45 a.m. and we’ve probably been in the air for about an hour and forty-five minutes. The fuel panel shows the tanks are still fairly full. I don’t know why I took this picture, except perhaps to show some part of the aircraft for a reason I’ve long since forgotten.

Here’s the front office. The panel is fairly standard, with flight instruments in front, two rows of engine gauges to the right of them. And in the center a stack of Garmin radios. We have two transponders, so as per Murphy’s Law, we will never, EVER have a transponder failure.

The equipment which probably looks most foreign to the pilots among you are the camera and the red LED-thingie above the annunciator panel. The camera is so we don’t miss any breaking news from CNN about new TFRs. And the LEDs are for the laser light show which accompanies the flying music on our iPods.

Um, or not. Actually, the camera allows is to verify that flies are actually dropping from the aircraft. The light bar on top of the glareshield is part of the AGNAV system. This system was originally designed for cropdusting. It indicates how far off the desired flight path we are at any given moment.

In the photo below, it indicates our ground track is 181 degrees true, and that we’re 64 feet to the right of the course centerline. The LEDs in the middle are a form of Course Deviation Indicator. Cropdusters need this because they can’t be looking down at a computer screen when they’re flying 10′ off the ground.

Here’s a wider photo of the entire panel, which I undoubtedly took on my way back from the ‘loo. Yeah, if only. We don’t have a bathroom onboard this aircraft. I was probably checking the fly box to get an idea of how much longer we’d be in the region dropping flies.

Anyway, the light bar now indicates we’re flying a true ground track of 3 degrees and are 41 feet right of the desired course line.

We are required to keep the aircraft within 150′ of the course line, 100’ of the desired altitude, and maintain 140 knots indicated airspeed +0/-5 knots. That’s not hard to do… for a while. But try doing it when you’ve been in the air for seven hours already. Fatigue? Yeah, it gets tiring.

Thankfully, we have two pilots on board and can switch off. That’s not to say the PNF (pilot-not-flying) can just sit around. The PNF has to operate the radios, scan for traffic, operate the dispersal equipment, monitor the pilot who is doing the flying, and do the required paperwork for each pass.

Here Tim is flying the aircraft while I’m… well, apparently taking a photograph. Keep in mind most of our operations take place in the Los Angeles basin, the most highly congested airspace in the world. We operate close to terrain, at low altitudes under the LAX localizer, and in all sorts of odd places you don’t normally find airplanes. We need to do that to ensure a proper coverage of medflies. I believe we drop them at the rate of something like 32,500 flies per linear mile.

The system works well, but it does require a high level of vigilance from the pilots. The Los Angeles airspace was not designed to accommodate our kind of flying, but what we do is important enough that the controllers have maps of our regions and we have an excellent working relationship with them, often operating in Bravo airspace where other aircraft would not be allowed entry.

When we reach the end of a line (or “pass”, as we call it), we reverse course and fly the next line according to the data provided by the CDFA. Most of our regions are flown on north/south or east/west courses, but occasionally terrain will dictate an oddball course, such as out by Lake Elsinore.

Anyway, here we are in the middle of a right turn. Notice the attitude indicator, which shows about a 50 degree bank. Pretty steep for a King Air. We are allowed up to 60 degrees of bank by company policy. It’s hard on the airplanes, and they’re old. And we fly in heavy turbulence at times. So the aircraft get frequent spar inspections.

I don’t know the details, but General Electric apparently has a division that does this type of inspection using some high tech equipment. I’ve seen the van come out and do something to the airplanes, but I’ve never paid enough attention to really know all the details. However, I take comfort in knowing that the same mechanics who turn wrenches on these aircraft also fly them.

Well, after a couple of hours on station, I go back and check the fly box to see what’s left. In this photo you can just see some residual flies clinging to the side of the box. They don’t fly around — remember, it’s 40 degrees in that box. They just sit there, even when the box is opened up. Looks like we’re out of flies, so it’s time to head back to base to refuel, take a 20 minute lunch break, and then do it all over again.

At the end of the day, the aircraft has to be refueled, post-flight inspection completed, cockpit secured, the augers cleaned out, paperwork completed, and more. When we’re done, the ramp looks neat and tidy:

It’s worth noting that not everyone at Dynamic gets to fly every day. There are two types of pilots: those who are mechanics, and those who aren’t. I’m a part-time, non-A&P captain, which means I fly all the time I’m there. Full-time mechanic/pilots split their work week, half the time in the air, and half on the ground doing maintenance work on the fleet:

Anyway, we’re pretty much done with work by 4:00 p.m. or so. Sometimes bad weather will cause us to work later than scheduled and we won’t get out of there until 5:00 or so, but that’s a rarity. We clock out, and voilia! The day is done.

Great post and a very interesting subject

Terrific post, I learned lots of new stuff from this one! 🙂

Combating nature with nature – and AIRPLANES!

as a controller at SoCal TRACON, i have been talking to you guys for years (the regions worked by 124.65, 127.2, 121.3 and 124.1), and this post taught me more than i ever knew about your operatioin. thanks!

Kevin, I’m glad you found my site! I also fly out of Sunrise Aviation at SNA (the Decathlons, Pitts, and Extra coming and going from the Blockhouse, as well as other airplanes). So I’ve probably talked to you on a hundred different occasions!

I live one block north of the base, and see/hear you guys coming and going all day. I used to wonder what your operation was (my first guess was training), but then I started listening to the tower freq and heard your “medfly” callsign. A little Internet searching revealed what you do, but this blog has taught me lots more, and is very interesting. Thanks!

I’m an inactive private pilot, but still an airplane nut, and am envious of your job. I haven’t flown in years, and really miss it.

I have a couple of questions. Did Dynamic used to fly Beech 18’s, or something like it? I seem to recall seeing them with “K&E Aircraft” painted on the side. What’s the story there? Who is K&E Aircraft?

Thanks again for a very interesting post! Loved the photos, too!

Hello Richard — I’m glad you enjoy the sight and sound of our King Airs! We try hard to abate as much of the noise as possible, especially since we launch out of Los Alamitos as early as 7:30 a.m.

Anyway, in answer to your question, yes, Dynamic used to operate Beech 18s out of that base. They were turbine conversions, meaning the standard radial engines were replaced with PT-6A turboprops. They got rid of the last of them about two years ago. I think the reason was because parts were getting hard to obtain. Beech stopped making the -18 a long, long time ago, whereas the King Air is still in production.

Dynamic also operated DC-3s converted for spraying, if you can believe that. I wish I would have had the opportunity to fly the Beech 18s — they look like a lot of fun!

A lot of Dynamic airplanes used to have “K&K Aircraft” written on them. I’m not sure what the relationship is, but I think it was the precursor to Dynamic Aviation. Dynamic is involved in many types of operation. Oil spill recovery, aerial data acquisition, mosquito spraying, you name it.

I would like to correct/clarify a few of the points made in this blog. The Medfly Preventive Release Program is as stated “preventative” and not used to “control” an established fly population. There is not at this time any infestation within the program boundaries. If there were, we would establish an “eradicative” program but at no time are we “controlling” a population. The Medfly is known to affect around 260 different crops, around 170 of which are grown in California. The cost of the program varies, but is currently around 13 million dollars annually. If medfly were to become permanently established in California, the estimated losses would approach 2 billion annually. It was not Malathion that affected vehicle’s paint but rather the sugary bait mixed with the pesticide. Sterile insect technique has not replaced the use of pesticides but is rather a component of integrated pest management. If a infestation of Mediterranean or Mexican fruit fly is detected within the state, an organic compound, Spinosad, is applied by ground to the target area to knockdown the population and sterile male flies are released by air to mate with fertile female flies. Dynamic Aviation is contracted by the USDA, not the CDFA. Also, responding to another posted reply, K&K Aircraft was the former name of Dynamic Aviation and readers should know that DC-3s were utilized for mosquito, not medfly, control.

Thanks for the clarification, Ian!

I just love the KingAir! I used to fly on the 350 series once and it was superb! A very good story btw!

Hey Ron, got another question.

When you guys check in with SoCal departure, you usually say what “region” you’re going to — region 32, 36, or something like that. What are these regions?

The regions are simply blocks of airspace. It’s not an FAA thing, it’s something set up for the Medfly program by the CDFA.

However, we fly every day, so the FAA controllers have been provided with an overlay of where those regions are. They can press a button and see our region map on their screen. This makes communicating with them much easier.

The map is not a secret, but neither is it published anywhere that I know of. The regions are numbered 1 through 33, and consist of either north/south or east/west passes. We use a GPS-based device called an AgNav (which was originally designed for crop dusting) to fly the specific passes requested by the CDFA.

We also have temporary regions setup anywhere they find a specific number of wild Medflies. Recently we’ve had such regions in Escondido, Mira Mesa, and down by Brown Field. A year or so ago, we had regions in San Jose and near Travis AFB.

The job requires an interesting mix of creativity, precision, and diplomacy when dealing with the controllers. We have to try our best to fly what the CDFA wants while still being considerate of ATC’s operations. We virtually cannot operate without their assent.

Right now, many of the controllers are trainees. Also, at times certain frequencies are combined and larger parcels of airspace are worked by a single controller. Some controllers are comfortable with things that others are not. You get to know the voices on the frequency. Perhaps they do as well. 🙂

Weather plays a big factor, too. When LAX and/or Ontario are landing to the east, John Wayne to the north, etc. it causes a lot of headaches for the controllers, and that can impact our operations. So sometimes we fly higher. Or lower. Or we fly a different region. We cannot drop flies if the OAT is below freezing, and we have to fly the regions under VFR, although we do make use of IFR-to-VFR-on-top quite a bit.

: I’ve seen these planes flying quite often in the Los Angeles area, now I know they’re purpose.

I am communications enthusiasts and I hear them communicating with LAX approach frequencies every so often.

You learn something every day, and this is quite interesting.

May the skies be with us.

Anthony

? ? ? ? ? ?